Initiating the massive transfusion protocol (MTP) is generally easy. Some centers use the Assessment of Blood Consumption score (ABC). This consists of four easy parameters:

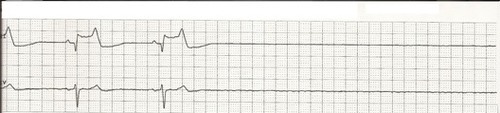

- Heart rate > 120

- Systolic blood pressure < 90

- FAST positive

- Penetrating mechanism

The presence of two or more indicators reliably predicts a 50% chance of needing lots of blood.

The shock index (SI) is also used. It’s more quantitative, just divide the heart rate by the systolic blood pressure. The normal value is < 0.7. As it approaches 0.9, the risk for massive transfusion doubles. This technique requires a little calculation, but is easily doable.

Or you can just let your trauma surgeons decide when to order it. Unfortunately, this sometimes gets forgotten in the mayhem.

However it got started, your MTP is now humming right along. How do you know when to stop? This is much trickier, and unfortunately can’t be as easily quantified. Here are the general principles:

- All surgical bleeding must be controlled. Hopefully your patient didn’t get too cold or acidotic during the case, resulting in lots of difficult to control nonsurgical bleeding (oozing).

- Hemodynamics are stabilizing. This doesn’t necessarily mean they are quite normal yet, just trying to approach it.

- Vasopressors are off, or at least being weaned.

- Volume status is normalizing. You may need an echo to help with this assessment.

If you have TEG, it probably wasn’t very useful. Until now. This is the ideal time to run a sample so you can top off any specific products your patient might need.

If you don’t have TEG, get a full coag panel including CBC, INR, PTT, lytes with ionized calcium.

Once the patient is in your ICU, continue monitoring and tweaking their overall hemodynamic and coagulation status until they are approaching normal. Then watch out for additional insults or any new and/or unsuspected bleeding. If this does occur, the threshold for return to the OR should be low. Unfortunately it is common for arteries in spasm to resume bleeding after warming and vasodilation.

When you are finally satisfied that there is no more need for the MTP, let your blood bank know so they can start restocking products and getting ready for the next go around!