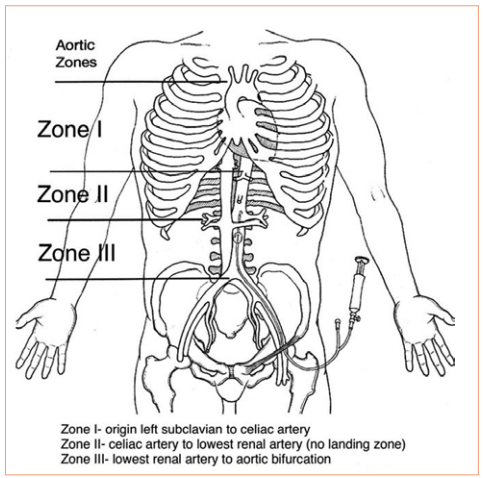

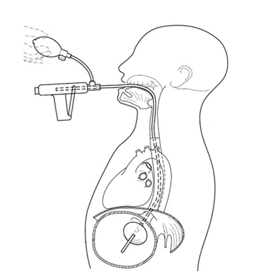

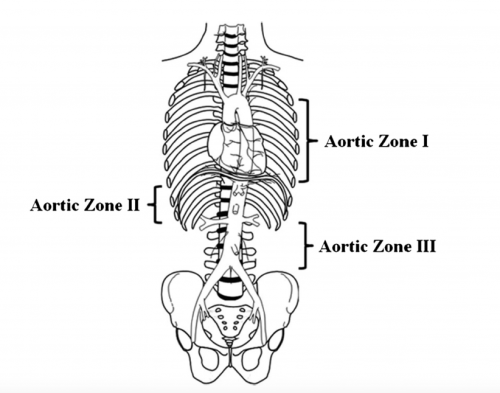

Papers for Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) use in trauma patients have been accumulating for the past decade or so. There are three zones within the aorta, and the REBOA balloon can be inflated in either Zone II for abdominal vascular injuries or Zone III for pelvic bleeding. Here’s a nice diagram for reference:

The original studies focused on Zone II deployments, but over the past five years or so there has been growing focus on using REBOA in Zone III. Pelvic arterial bleeding can be quite problematic, and if the patient is hypotensive in the emergency department, it is not permitted to take them to interventional radiology for management. The only choice is a trip to OR for preperitoneal packing or some less effective procedure. With the use of Zone III REBOA, it became possible to stabilize vital signs and then allow transport to IR or hybrid OR for angioembolization.

After the initial rush of very positive research, more recent papers are a bit more tempered with results that are not as cut and dried. This abstract from Hartford Hospital attempts to add a bit more information about the use of Zone III REBOA in patients who required a hemorrhage control procedure. The authors performed a retrospective review of four years of TQIP data. They compared outcome data in hypotensive adult patients with pelvic fractures requiring some type hemorrhage control procedure. The authors divided patients into REBOA+ and REBOA- groups, and looked at mortality, blood utilization, lengths of stay, and REBOA complications.

Here are the factoids:

- Of the 4,453 patients who met inclusion criteria, only 139 patients underwent Zone III REBOA

- The REBOA+ patients had lower BP and GCS and ISS was higher prompting the use of propensity matching

- In order to equalize comparisons patients were propensity matched the the variables listed above, yielding 121 pairs for study

- In-hospital and 24-hour mortality were double in the REBOA+ group (50.5% vs 25% and 31% vs 14.3%, respectively)

- Blood transfusion was also higher in the REBOA+ group (median 4L vs 1.75L)

- AKI was higher in the REBOA+ group (16% vs 7%) but the amputation rates were the same (no numbers given)

The authors concluded that Zone III REBOA appears to have worse outcomes and suggest that more prospective studies are indicated.

Bottom line: I have been a REBOA skeptic for some time so I have to be careful not to feed my confirmation bias. Many of the previously published positive papers include authors who have a relationship with one of the major REBOA device manufacturers. Papers from centers without any conflicts of interest are generally less positive.

Despite my own bias I also have some major questions about this abstract. The biggest thing is that I can’t make the statistics work. Granted, the entire analysis is not in the abstract. But the mortality rates given in percentages don’t yield integers when multiplied by the 121 patients in each group.

This makes me worry that we are not seeing all the statistics and we are somehow getting relative risk rather than absolute risk. I’m also confused about why the SBP, ISS, and GCS matched groups would have a difference in AKI rates in addition to the mortality numbers. Are there other significant variables affecting morbidity and mortality that were not identified or controlled?

Here are my comments and questions for the authors / presenter:

- Review the mortality calculations for us. How can you have a hospital mortality rate of 50.5% with 121 patients (= 61.105 people)? Provide the absolute mortality numbers so we can do the math.

- Why are the transfusion numbers so much higher in the REBOA+ group? Isn’t this device supposed to reduce bleeding? It seems unlikely that REBOA is making them bleed more. Is there something else going on?

- Similarly, why would AKI be higher in REBOA+ patients? The balloon is located below the kidneys and they should benefit from better perfusion.

- Could there be other factors not analyzed that contributed to the poorer outcomes in the REBOA+ group? What might they be?

I suspect the snapshot that the TQIP data allows may not be enough to let us see the entire picture here. I am looking forward to additional information during the presentation to help clarify these issues.

Reference: DOES THE USE OF REBOA IMPROVE SURVIVAL IN PATIENTS WITH PELVIC FRACTURES REQUIRING HEMORRHAGE CONTROL INTERVENTION? AAST Plenary paper #46, AAST 2022.