Although very few things in medicine are new, I love it when I learn about something I’ve never heard of before. Recently, while reading an autopsy report, I ran across the term “hinge fracture of the skull.” What? Maybe if I were a neurosurgeon, I would have recognized the term. This was the perfect excuse to hit the books (or, more accurately, the internet).

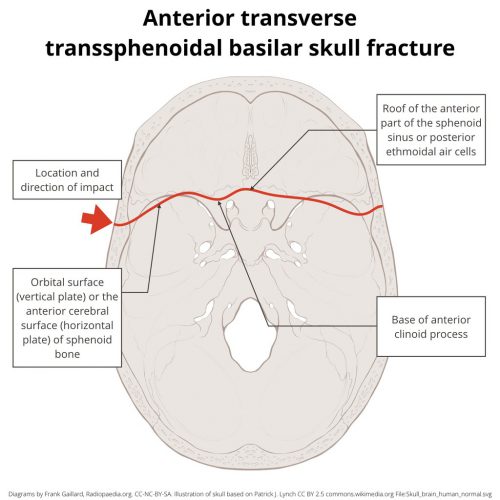

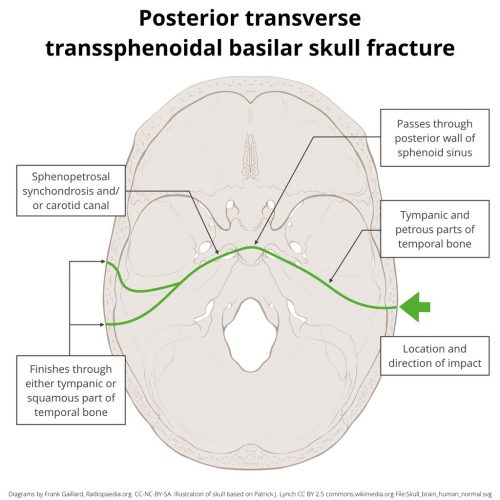

A hinge fracture crosses the skull base transversely and involves the temporal and sphenoid bones. Here are diagrams of two common transsphenoidal fracture patterns, courtesy of radiopaedia.org. The red and green lines can be considered transverse (hinge) fractures.

Why the hinge analogy? Since the fracture extends entirely across the skull base, it splits the skull in two. In theory, the bones could hinge around this line, but the reality is that it usually doesn’t. It’s just a memorable name.

It takes a significant amount of force to fracture the skull like this. Although any major blunt force could do this, there is a higher association with motorcycle crashes. I found an interesting paper (cited below) that showed that if a rider’s face smashes into the back of the cycle driver, the force delivered to the rider’s mandible can cause this fracture pattern. It can also occur in falls from heights and direct trauma to the head (e.g., baseball bat).

Many patients with this injury do not survive very long due to severe CNS injury or other significant blunt-force injuries. Those who do may demonstrate these findings on exam:

- Bruising typical of a skull base fracture. This includes Battle’s sign (bruising behind the ears over the mastoid process) and raccoon eyes (bruising around the eyes).

- Evidence of severe TBI. Low GCS is expected due to significant force to the head.

- Cranial nerve deficits. The path of the fracture can vary considerably and may involve one or more cranial nerves. Patients may manifest hearing loss, double vision (if awake), or facial paralysis.

- CSF leak. Many basilar skull fractures result in otorrhea or rhinorrhea, and this one is no exception.

If your patient survives the trauma bay, diagnosis is made by CT scan. Given the location of this fracture, CT angiography should be added if a hinge fracture is identified. There is a higher probability of blunt carotid and vertebral arterial injury with this diagnosis.

Treatment of this fracture complex is beyond the scope of this post. Consult your friendly neighborhood neurosurgeon. Only they can appreciate the nuances and reconstructive needs of this injury.

Reference: Mechanism of transverse fracture of the skull base caused by blunt force to the mandible. Legal Medicine,

Volume 54, 101996, 2022.