Early availability of blood is a key component in the successful resuscitation of severely injured trauma patients. All trauma centers have implemented massive transfusion protocols (MTP) to ensure rapid delivery of blood products to the trauma bay.

Unfortunately, locating the blood bank in some remote corner of the basement is common practice, as far from the trauma bay as possible. This guarantees a delivery delay once the MTP is activated. To offset this, many centers have implemented policies to make a limited quantity of blood products available in the trauma bay.

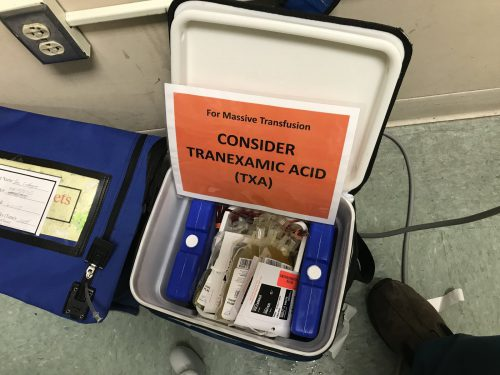

This supply can be located in a blood refrigerator located nearby. Or it may be a practice of calling for emergency release blood if the trauma professionals believe it might be necessary. Some trauma centers have codified this so that highest-level activations automatically have a cooler of blood products delivered, hopefully before patient arrival.

However, I have observed while visiting numerous centers that this often causes an unintended consequence. It can actually slow MTP activation!

How can that be, you say? It’s simple. Critically injured patients result in an intense and highly charged trauma activation. The surgeon is concentrating on keeping the patient alive and orders the emergency release blood to be hung. The resuscitation continues. “Hang another unit.” And so on.

Eventually, the temporary supply runs out. Then everybody looks at each other and does a facepalm. Nobody thought to activate the MTP!

How can this be avoided? The key is to do everything possible to activate it from the very start. Here are some tips:

- Use an objective scoring system to trigger MTP. The two most common ones are the ABC score and the Shock Index. Both are easy to calculate, and can frequently be used based on the prehospital report. This means the MTP can be activated before the patient even arrives.

- If you open the blood refrigerator or touch the emergency release blood, activate the MTP. This will give you two to four units to buy time for the first MTP cooler to arrive.

- Empower everyone in the trauma bay to speak up. Make sure everyone knows the rules listed above, and encourage them to speak up if they see that any of them are met. “Team leader, should we activate the MTP?”

- Don’t be shy! If you only transfuse one unit of refrigerator blood and stop, no harm, no foul. The unopened MTP cooler can be sent back to the blood bank with no risk of waste.

Bottom line: Don’t get suckered into forgetting to activate the MTP just because it looks like you have blood available. Automate the process so you never run out again.