More stuff on TXA! I published two posts back in December on TXA hesitancy. This Friday, the trauma group at Wake Forest is presenting an abstract on TXA use by prehospital trauma professionals.

It is very likely that EMS carries tranexamic acid (TXA) in your area. Each agency has its own policy on when to administer, but the primary indication is hemorrhagic shock. A few ALS services may infuse for serious head injury as well.

The Wake Forest group was concerned that TXA administration might be occurring outside of the primary indication, hemorrhagic shock. They reviewed their experience using a six-year retrospective analysis of their trauma registry. The patients’ physiologic state before and after arrival at the hospital was assessed, as were the interventions performed in both settings.

Here are the factoids:

- Of 1,089 patients delivered by 20 EMS agencies, one-third (406) had TXA initiated by EMS

- Only 58% of patients who received prehospital TXA required transfusion after arrival

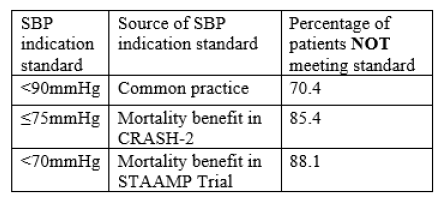

- TXA administration based on BP criteria were as follows:

- Similar compliance was noted when examining only high-volume EMS services

The authors concluded that TXA use is common in the prehospital setting but is being used outside of literature-driven indications.

Bottom line: This is an interesting snapshot of TXA use surrounding a single Level I trauma center. As such, it can’t be automatically applied to all. However, my own observations suggest that this drug is being used more liberally nationwide.

Clearly, the prehospital providers are starting TXA on patients who do not fit the category of severe hemorrhagic shock. Only 30% of patients receiving it had SBP < 90. Is this a bad thing? Referring back to my conversation on TXA hesitancy, I think not. But do keep in mind that giving any drug when not indicated adds no benefit and can certainly increase risk. The good news is that TXA is very benign when it comes to side effects.

However, policies are designed for a reason: safety. And if the EMS agency policy says to give TXA only for SBP < x, then that’s when it should be given. The prehospital PI process (or the trauma center’s) should identify variances and work to correct them. If EMS is “overusing” TXA in your area, your trauma center should add this as a new prehospital PI filter and let them know when it happens.

Here are my questions and comments for the presenter/authors:

- Is using the need for transfusion a valid measure of the need for TXA? You found that half of the patients receiving TXA were not transfused. The decision to transfuse depends on surgeon preference, and they don’t always use objective criteria. And hey! Maybe the TXA worked, obviating the need for blood!

This is a straightforward and intriguing paper. I’m excited to hear more details on how you sliced and diced this data.

Reference: ARE DATA DRIVING OUR AMBULANCES? LIBERAL USE OF TRANEXAMIC ACID IN THE PREHOSPITAL SETTING. EAST 2023 Podium paper #34.