A bucket-handle injury is a relatively uncommon complication of blunt trauma to the abdomen. It only occurs in a few percent of patients, but is much more likely if they have a seat belt sign. The basic pathology is that the bowel mesentery (small bowel of sigmoid colon) gets pulled away from the intestinal wall.

This injury is problematic because it may take a few days for the bowel itself to die and perforate. Patients with no other injuries could potentially be discharged from the hospital before they become overtly symptomatic, leading to delayed treatment.

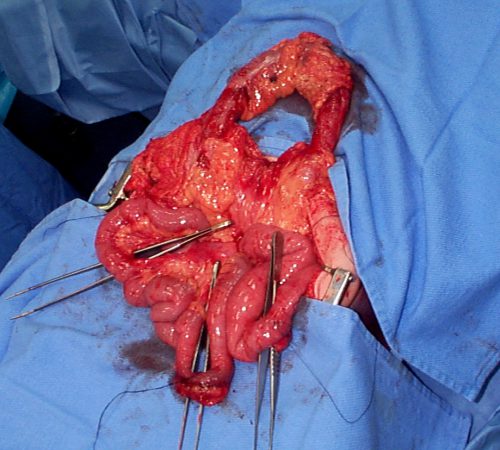

Here’s an image from my personal collection with not one, but four bucket-handle injuries.

Typical patients with suspected blunt intestinal injury are observed with good serial exams and a daily WBC count. If this begins to rise after 24 hours, there is a reasonable chance that this injury is present.

CT scan has not really been that reliable in past studies. There may be some “dirty mesentery”, which is contused and has a hematoma within it. But without a more convincing exam, it is difficult to convince yourself to operate immediately on these patients.

A paper was published by a group of radiologists at Duke University. It appears to be a case report disguised as a descriptive paper. It looks like they picked a few known bucket-handle injuries from their institution and back-correlated them with CT findings.

The authors called out the usual culprits:

- Fluid between loops of bowel

- Active bleeding in the mesentery

- Bowel wall perfusion defects

But they also noted that traumatic abdominal wall hernias were highly with the injury as well. These are rare, but should bring intestinal injury to mind when seen.

With newer scanners, radiologists are better able to detect subtle areas of hypoperfusion as well. This is a fairly good indicator of injury, especially when adjacent bowel appears normally perfused. Here are two examples. The black arrows denote active extravasation, and the white ones an area of hypoperfusion.

The authors add bowel wall hypoperfusion as another finding that may point to a bucket-handle type injury

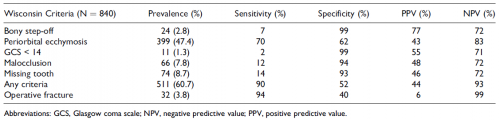

Bottom line: Hold the phone! Don’t change your practice yet. This paper is not able to demonstrate how good this radiographic sign is. Looking at other radiology literature, the specificity is about 90%. But remember, that means that if they don’t have the CT finding, that’s true only 90% of the time.

Unfortunately the sensitivity is only 10%. So if you see it on the scan, they’ve got a 1 in 10 chance of actually having the injury. That’s not good enough for me to run to the operating room.

Here’s what I recommend: if your patient has an unconcerning exam and any of the usual culprits (pelvic fluid, inter-loop fluid, dirty mesentery, thickened bowel loops, abdominal wall hernia), perform serial exams and get a WBC the next morning. If the exam worsens, operate. If the WBC rises, consider laparoscopy to see if you need to make a bigger incision. And if you see this new kid on the block, the hypoperfused bowel, consider laparoscopy right away.

I’m sure the radiologists and the technology will keep getting better. But for now, blunt intestinal injury still requires patience, perceptiveness, and a little luck.

References:

- CT findings of traumatic bucket-handle mesenteric injuries. Am J Radiol 209:W360-@364, 2017.

- Multidetector CT of blunt abdominal trauma. Radiology 265(3):678–693, 2012.