Look out, radiologists! The computers are coming for you!

Radiologists use their extensive understanding of human anatomy and combine it with subtle findings they see on x-ray shadow pictures. In doing this, they can identify a wide variety of diseases, anomalies, and injuries. But as we have seen with vision systems and game playing (think chess), computers are getting pretty good at doing this as well.

Is it only a matter of time until computer artificial intelligence (AI) starts reading x-rays? Look at how good they already are at interpreting EKGs. The trauma group at Stanford paired up with the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taiwan to test the use of AI for interpreting images to identify a specific set of common pelvic fractures.

The Stanford group used a deep learning neural network (XCeption) to analyze source x-rays (standard A-P pelvis images) from Chang Gung. These x-rays were divided into training and testing cohorts. The authors also applied different degrees of blurring, brightness, rotation, and contrast adjustment to the training set in order to help the AI overcome these issues when interpreting novel images.

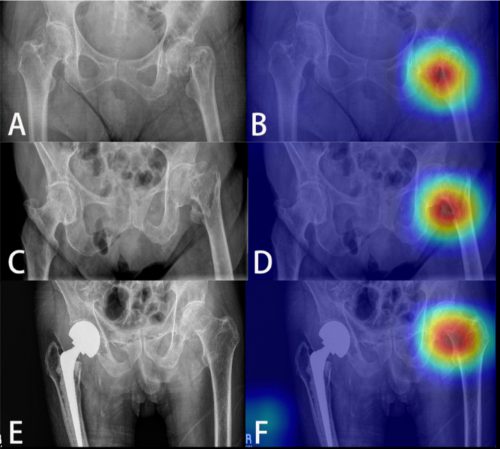

The AI interpreted the test images with a very high degree of sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and predictive values, with all of them over 0.90. The algorithms generated a “heat map” that showed the areas that were suspicious for fracture. Here are some examples with the original x-ray on the left and the heat map on the right:

The top row shows a femoral neck fracture, the middle row an intertrochanteric fracture, and the bottom row another femoral neck fracture with a contralateral implant. All were handily identified by the AI.

AI applications are usually only as good as their training sets. In general, the bigger the better so they can gain a broader experience for more accurate interpretation. So it is possible that uncommon, subtle fractures could be missed. But remember, artificial intelligence is meant to supplement the radiologist, not replace him or her. You can all breathe more easily now.

This technology has the potential for broader use in radiographic interpretation. In my mind, the best way to use it is to first let the radiologist read the images as they usually do. Once they have done this, then turn on the heat map so they can see any additional anomalies the AI has found. They can then use this information to supplement the initial interpretation.

Expect to see more work like this in the future. I predict that, ultimately, the picture archiving and communications systems (PACS) software providers will build this into their product. As the digital images are moving from the imaging hardware to the digital storage media, the AI can intercept it and begin the augmented interpretation process. The radiologist will then be able to turn on the heat map as soon as the images arrive on their workstation.

Stay tuned! I’m sure there is more like this to come!

Reference: Practical computer vision application to detect hip fractures on pelvic X-rays: a bi-institutional study. Trauma Surgery and Acute Care Open 6(1), http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tsaco-2021-000705.