In most hospitals, it seems that workers in every department wear a different color of scrubs. Traditionally, surgeons have worn scrubs in darker shades of green or blue. This is not always true, as some hospitals have adopted crazy colors in order to reduce theft. Apparently, not too many people are comfortable wearing a pilfered pair of bright pink scrubs in public.

We know that color can have subliminal impacts on people. Blue tends to have a calming effect. This is one of the reasons that police officer uniforms are frequently this color. Green and blue also tend to be associated with medicine. Red, orange, and yellow are often associated with food. Ever wonder why McDonald’s arches are the color they are?

But what about scrubs? Patients do tend to form associations between a clinician’s dress and their intelligence, empathy, and trustworthiness. Interestingly, scrubs (as opposed to dress clothes) score high for all of these.

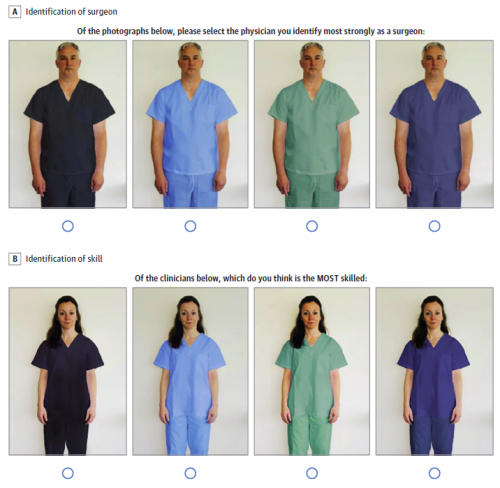

But what about the rainbow of colors that scrubs are available in? A recent research letter was submitted to JAMA Surgery by a group at UNC Chapel Hill. They administered an electronic survey over a two-month period to adult patients and visitors at their university hospital. Their goal was to determine whether scrub color influenced the perception that the wearer was a surgeon, and what character traits were perceived.

This is a copy of the survey, asking for the identification of the surgeon, and the most skilled individual based on scrub color.

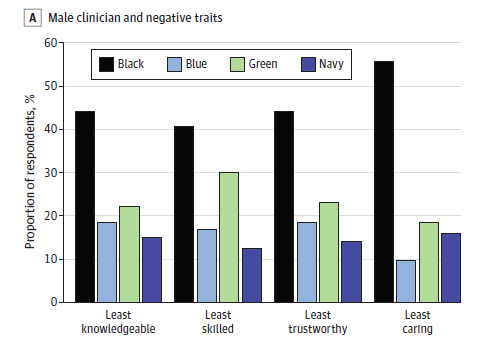

The results were quite interesting. This is a chart of trait identification based on color for men. The chart for women was very similar. Note that taller bars are a negative.

Here are the factoids:

- Half of participants were 30-60 years old, and the remainder were evenly split between younger and older people

- Green was the color most associated with surgeons and was selected by nearly half of participants. Sex did not seem to matter.

- Black had the most negative connotation of any color

- Blue scrubs were associated with the most caring clinicians; however it also implied that they were less knowledgeable, less skilled, and less trustworthy

Bottom line: This is an intriguing little study that shows that unfortunately, looks do matter. Even the colors of our clothes do! The participants associated black with death and said they looked like a mortician’s uniform. So definitely avoid!

The poor perception of clinicians wearing green scrubs is difficult to explain, but consistent. The navy and blue characteristics were generally positive and don’t look appreciably different from each other.

Hospitals pay little attention to the color of the scrubs they purchase. But this choice may have an impact on how the wearer is perceived by patients and families. Perhaps it is time to rethink color in patient-facing clinicians. And avoid black scrubs like the plague!

Reference: Association Between Patient Perception of Surgeons

and Color of Scrub Attire. JAMA Surg, 2023 Jan 11. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.5837. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36630142.