The pendulum has swung from the use of whole blood in the early 20th century, to component therapy in the 1960s, and now a gradual move toward incorporating whole blood again. More and more papers are being published, and many trauma centers are looking for ways to integrate whole blood into their massive transfusion protocols.

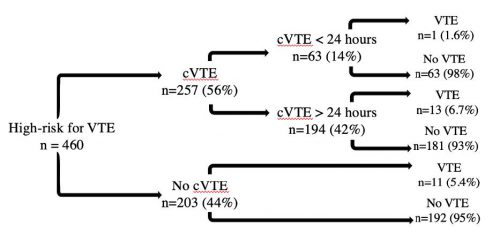

Much of the literature has been dedicated to safety and effectiveness, but little has examined thrombotic complications from its use. The trauma group at the University of Texas in Houston performed what looks to be a retrospective review of whole blood usage at two Level I trauma centers. Adult patients receiving at least one emergency-release whole blood unit were compared with those receiving only component therapy. They looked at the incidence of venous thromboembolic (VTE) complications such as pulmonary embolism (PE) or deep venous thrombosis (DVT).

Here are the factoids:

- Nearly 3,500 patients were enrolled and were fairly evenly split between whole blood and component therapy only

- Whole blood patients were slightly younger, were much more likely to have penetrating injury, and had significantly higher ISS (26 vs 19)

- The whole blood patients were also significantly more likely to receive TXA, VTE chemoprophylaxis within 48 hours (86% vs. 79%) and lower 30-day survival (74% vs 84%)

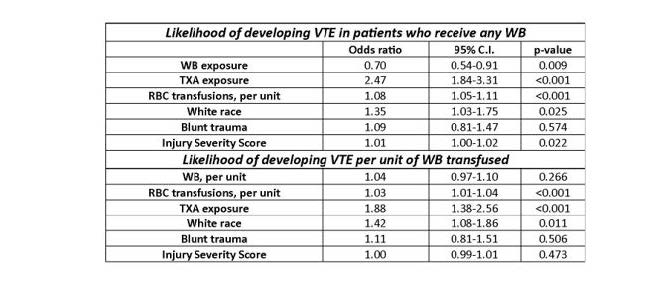

- Crude incidence of VTE was similar (7% whole blood vs. 9% component), but logistic regression “revealed that whole blood was protective of VTE,” while red cell transfusion and TXA increased VTE risk

- Each unit of red cells increased VTE risk by 3%

The authors concluded that whole blood was associated with a 30% reduction in VTE, and TX was associated with a 2.5x increase in risk. They cautioned against the use of TXA in the setting of whole-blood resuscitation.

Bottom line: A lot is going on here. First, this is a retrospective study, which limits the number of variables that can be collected reliably. It also makes it much more difficult to perform regression analysis because there are many other possible variables to control for than just the ones collected.

Next, as quoted in bullet point 4 above, this study can’t show that whole blood was protective, only that it was (maybe) associated with decreased VTE when the variables they collected were controlled.

Most of the confidence intervals for the “significant” results were very close to the 1.0 line. This leaves the possibility that the result could easily be changed by adding other pertinent variables not included in the data. The only impressive one was the association of TXA exposure and VTE. I think this demands further work.

The authors need to answer several questions in their presentation to help explain the results:

- Was there any relationship between the number of units of packed cells given and the likelihood of VTE?

- Similarly, was there a relationship between the number of units of whole blood and possible “protection” from VTE?

- Did you examine other physiologic or anatomic variables and their relationship with VTE? Specific ones that come to mind are shock, long bone or spine fractures, and TBI. These are some of the variables that need to be included in the regression model to improve it.

Overall, this is an interesting abstract that makes one think. But it either needs some good explanations during the presentation or additional data analysis to make it even more interesting.

Reference: Does whole blood resuscitation increase risk for venous thromboembolism in trauma patients? A comparison of component therapy vs whole blood in 3468 patients. EAST 2024, Podium paper 33.