Facial trauma is common, especially in children. And the use of CT scan is even more common, unfortunately for children. What happens when these two events meet?

I’ve noted that many trauma professionals almost reflexively order a face CT when they see any evidence of facial trauma. This ranges from obvious deformity to lacerations to mere contusions. This seems like overkill to me, since most of the face (excluding the mandible) is visualized with the head CT that nearly always accompanies it.

Finally, someone has actually examined the usefulness of the facial CT scan! The trauma group at Albany collaborated with four other Level I trauma centers, performing a retrospective chart and database review of children (defined as less than 18 years old) who underwent both head and maxillofacial CT scans over a five year period. They excluded penetrating injuries and bites. The concordance of facial fractures seen on head CT vs face CT was evaluated.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 322 patients with facial fractures was identified, and the most common mechanisms were MVC, pedestrian struck, and bicycle crash

- Fractures on head CT matched the facial CT in 89% of cases

- Of the 35 discordant cases, 21 of the head CTs missed nasal fractures, 9 mandibular fractures, 3 orbital fractures, and 2 maxillary fractures

- Of those 35 cases, only 7 required operative intervention: 6 mandible fractures and 1 maxillary fracture

The authors concluded that the use of head CT alone with a good clinical exam detects nearly all facial fractures requiring repair.

Bottom line: Although this study confirms my own personal bias and experience, it suffers from the usual problems associated with retrospective studies and small numbers. Nonetheless, the results are compelling. This study provides a way to identify nearly all significant fractures while minimizing radiation to the ocular lens, thyroid, and bone marrow.

The key is a good physical exam, as usual. Inspection of the teeth, occlusion testing, and manipulation of the mandible and maxilla should identify nearly all fractures that might require operation.

Once the exam is complete, a standard head CT should be obtained. Identification of displaced fractures on the head CT should prompt a consult to your friendly facial surgeon to see if they really need additional imaging to determine if the fracture requires operation. Frequently, the head CT images are sufficient and nothing further is required.

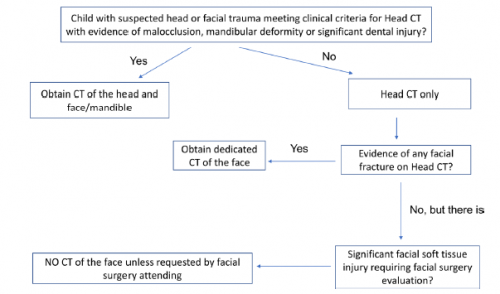

Here is the algorithm the authors recommend. Although designed for children, it should work for adults just as well.

Reference: Clinical and radiographic predictors of the need for facial CT in pediatric blunt trauma: a multi-institutional study. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2022;7:e000899.