All trauma centers admit some of their patients to nonsurgical services. This usually occurs when patients have medical comorbidities that overshadow their injuries. Unfortunately, the decision-making that goes into balancing the medical versus trauma issues is not always straightforward. The fear is that if trauma patients are inappropriately placed on a nonsurgical service, mortality and morbidity may be higher because their injuries may not receive adequate attention.

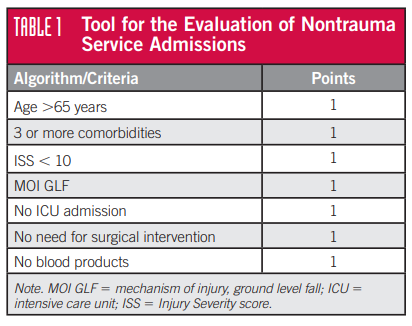

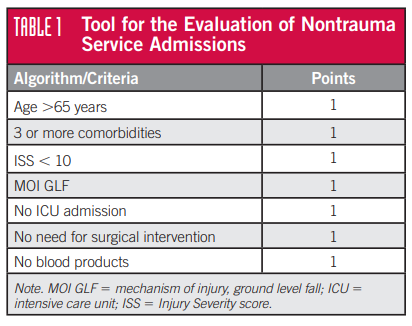

To take some of the variability out of the decision-making process for admitting service, two surgical groups on Long Island created a scoring system that incorporated several parameters described in the ACS Optimal Resource Document (Orange book). Some additional parameters were also included that the authors believed were relevant to the choice of admitting service. Here’s the final list:

The first author on the paper was a nurse, Laura Nelson, and hence this has come to be known as the Nelson Score. Patients with a score score of 7 were considered definitely appropriate for nonsurgical admission. Scores of 4 or 5 were subject to more in-depth review, and those with a score of 3 or less were considered definitely appropriate for trauma service admission. There is no mention of what to do with a score of 6 in the original paper, but I presume it should be almost a slam dunk for considering nonsurgical admission.

The authors evaluated this system’s utility over a two year period. They found that using it placed more patients on the trauma service (nonsurgical admissions decreased from a peak of 28% to somewhere around 10%). They also examined morbidity and mortality statistics between the two types of admissions, and found no significant differences.

The concept was further tested by the trauma group at UCHealth in Colorado Springs. They performed a retrospective review of four years of data that included over 2,000 patients. Patients were older (mean 79 years) and nearly all had blunt mechanism. Mean ISS was 9 and the nonsurgical admission rate was 19%. Patients with a Nelson score of 6 or 7 were even older and had more comorbidities.

Regression analysis did not identify admitting service as a predictor of mortality. The authors concluded that using this score is a safe way to objectively identify patients who would benefit from nonsurgical admission.

Bottom line: I have visited a number of hospitals that successfully use the Nelson score to assist with admission service decision-making while the patient is still in the emergency department. The only gray zone is the score of 4 or 5. Each program will need to determine their own cut point so they can make the service decision more objectively.

Trauma programs can also use this tool to expedite PI review of patients who have already been admitted to a nonsurgical service to check appropriateness. If the score is less than 6 further scrutiny is needed to determine if a consult from or transfer to trauma should be recommended.

References:

- Nonsurgical Admissions With Traumatic Injury: Medical Patients Are Trauma Patients Too. Journal of Trauma Nursing, 25 (3), 192-195, 2018.

- Evaluation of the Nelson criteria as an indicator for nonsurgical admission in trauma patients. Am Surg, 88(7), 1537-1540, 2022.