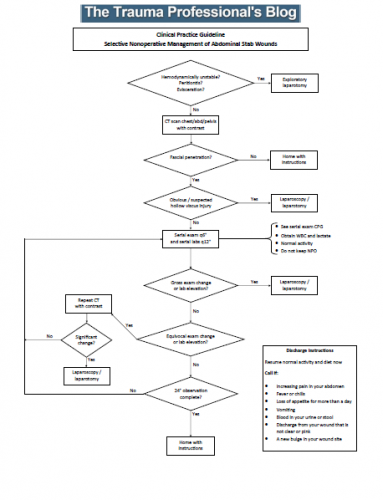

In my previous post, I reviewed a new paper that examined the appropriate amount of time that patients should be observed for nonoperative manage of an abdominal stab wound. Many of you know that I am a fanatic of properly crafted clinical practice guidelines (CPG). I decided to make a first pass at converting the LAC+USC group’s paper to something that will be helpful at the bedside.

This CPG incorporates the patient selection and timing information published in the paper. It breaks the process down into easily followed tasks, and fills in the blanks for shift to shift management. The CPG is displayed in an “if this, then do that” format. This firms up decision making and makes it easier for your trauma program to monitor compliance with it.

A note about CPGs: they generally cover about 90% of clinical cases. Obviously, they cannot provide guidance for certain rare combinations of circumstance. In that case, the trauma professional should do what they think is right for that situation. Most importantly, they should document this rationale in a progress note.

A note about CPGs: they generally cover about 90% of clinical cases. Obviously, they cannot provide guidance for certain rare combinations of circumstance. In that case, the trauma professional should do what they think is right for that situation. Most importantly, they should document this rationale in a progress note.

Here are answers to some of your questions in advance:

- Patients should not be kept at bed rest. This is always bad.

- There is no reason to keep the patient NPO. A very small percentage of patients actually fail. It makes no sense to starve everybody for the one or two patients that need to go to the OR each year. Anesthesiologists at trauma centers are very skilled at providing safe intubation in all patients. As you all know, every trauma activation patient coming into your trauma bay needing intubation has just finished a seven course meal!

- Give your patient clear discharge instructions! They need to know what they can do, and what to look for if things eventually go awry.

And please leave comments and suggestions for improvements in the reply box below or by email to [email protected]. There are always ways to make CPGs even better! I have also included a Microsoft Publisher file so you can modify this guideline to better suit your trauma center.

In my next post, I’ll publish the serial abdominal observation CPG I mention in this one.

Resources: