IVC filter insertion has been one of the available tools for preventing pulmonary embolism for decades—or so we thought. Its popularity has swung back and forth over the years and has been in the waning stage for quite some time now. This pendulum-like motion offers an opportunity to study effectiveness when coupled with some of the large datasets that are now available to us.

IVC filters have been used in two ways: prophylactically in patients at high risk for pulmonary embolism (PE) who cannot be anticoagulated for some reason and therapeutically once a patient has already suffered one. Over the years, guidelines have changed and have frequently been in conflict. Currently, the American College of Chest Physicians does not recommend IVC filters in trauma patients, and the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma just released a new practice guideline for them.

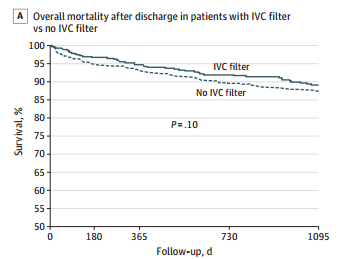

A previous study from Boston University reviewed its own experience retrospectively over a 9-year period. This cohort study looked at patients with and without filters, matching them for age, sex, race, and injury severity. The authors specifically looked at mortality and used four study periods during the 9-year interval.

Here are the factoids:

- Over 18,000 patients were admitted during the study period, resulting in 451 with an IVC filter inserted and 1343 matched controls

- The patients were followed for an average of 4 years after hospitalization

- Mortality was identical between patients with filters vs the matched controls

- There was still no difference in mortality, even if the patients with the filter had DVT or PE present when it was inserted

- Only 8% ever had their “removable” filter removed (!)

And now, there is a paper in press from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma with their newest practice guideline on IVC filters. They examined the literature on patients with or at risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) and sought to determine whether IVC filters should be used prophylactically or therapeutically in these situations. They reviewed twenty-one studies, most of which were of the usual low quality. They drew the following conclusions:

- IVC filters should not be placed routinely for prophylaxis in patients without DVT who cannot receive chemoprophylaxis.

- EAST conditionally recommends that IVC filters not be placed in patients with DVT who cannot receive prophylaxis. This recommendation was conditional due to the very poor quality of the few papers available to answer this question.

Bottom line: It looks like the end is near for the IVC filter. However, I can still foresee a few situations where there might be some utility. Consider the case where a patient has DVT, cannot be anticoagulated, and is showering emboli to the lungs. Otherwise, it appears that this device is on its last legs!

References:

- Association Between Inferior Vena Cava Filter Insertion

in Trauma Patients and In-Hospital and Overall Mortality. JAMA Surg, online ahead of print, September 28, 2016. - Role of Vena Cava Filter in the Prophylaxis and Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism in Injured Adult Patients: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Practice Management Guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, Publish Ahead of Print DOI: 10.1097/TA.0000000000004289, 2024.