I am trying to figure out how I missed it! The Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) snuck a new practice management guideline into the Injury journal last fall. And it desperately tries to answer a question that has been hanging around for several years. Do we vaccinate spleen injury patients who undergo angioembolization or not?

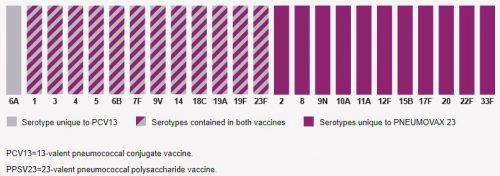

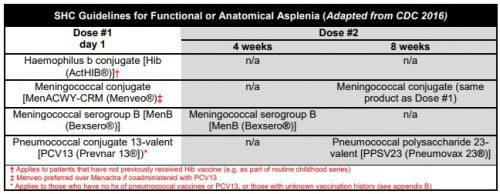

I’ve been pondering this for some time and have reached my own conclusion based on some very old literature. Decades ago, we figured out that removing the spleen significantly affects immune function. Splenectomy patients are known to be more susceptible to encapsulated bacteria like Neisseria meningiditis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae. Most trauma centers routinely vaccinate these patients before they are discharged home.

With the more recent emphasis on splenic salvage and nonoperative management of injury to this organ, angioembolization has become commonplace. This technique can be done in two ways: proximal and distal. Proximal embolization blocks the splenic artery, so there is no further blood flow to the spleen through it. Distal embolization (selective or super-selective) strives to block flow to very specific areas of the organ.

Do we need to give the vaccines if we cut off blood flow to pieces of the spleen or the main splenic artery? Based on my appreciation of very old splenectomy and partial splenectomy papers, it looked like we should in some cases. One report showed that splenic protection from encapsulated bacteria required about 50% of the spleen to be present and perfused by the splenic artery. This caveat stems from a time when we would perform a trauma splenectomy, dice the spleen up on the back table, and then implant a bunch of spleen cubes into the mesentery to try to provide some immune protection. Turns out that the pieces lived but didn’t do a damn thing.

My practice, then, has been to look at the fluoro images and estimate how much of the spleen was left. I would order the vaccines if a main splenic artery embolization (proximal) was performed. If a distal embolization were performed, I would eyeball the amount of devascularized spleen and give the vaccines if it looked like more than half was dark. Not very precise, I know.

But what would EAST say? They tried to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that compared outcomes in splenectomy vs. angioembolization patients. Unfortunately, there isn’t a lot of research material out there. So they settled on looking at papers that analyzed immune function, typically using B-cells, T-cells, and antibodies. The authors performed two comparisons: angioembolization vs. splenectomy and angioembolization vs. control.

Angioembolization vs. Splenectomy

These papers compared embolization patients who may or may not have spleen function to splenectomy patients who definitely have none. Embolization patients had fewer infectious complications during their hospital stay and better immune function using the indirect methods noted above. Unfortunately, the data quality was poor, with a significant risk of bias. There was no stratification of proximal vs. distal embolization. Nevertheless, this suggests that, at least overall, the embolization patients retained immune function.

Angioembolization vs. Controls

What about comparing embolization patients to spleen-injured patients who did not undergo any procedure? They should have normal function. Again, the quality of the very few papers available was low. But overall, there was no difference in immune function between the groups.

Bottom line: The EAST review team conditionally recommended against routine spleen vaccines after angioembolization for spleen injury. They concluded that immune function was maintained, so it should not be necessary.

What, you ask, about patients with proximal splenic embolization? The reality is that this only stops inflow from the splenic artery, and only for a few days or weeks. It may slowly resume over time. And it does nothing to the inflow from the short gastric arteries. Apparently, this is enough to provide immune protection against infection.

Whether this is actually true is open to debate. We have no idea if the numbers of T- and B-cells seen and the antibody titers are actually enough to avoid overwhelming post-splenectomy sepsis. And unfortunately, this condition is so rare that we will never accumulate enough cases to make a definitive statement.

But for now, it is probably okay to forgo the vaccines in patients undergoing angioembolization. Besides, the differing guidelines on which vaccines to use, when to give them, and when to schedule boosters were getting way out of hand! Please keep it simple!

Reference: Vaccination after spleen embolization: a practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. Injury 53:3569-3574, 2022.