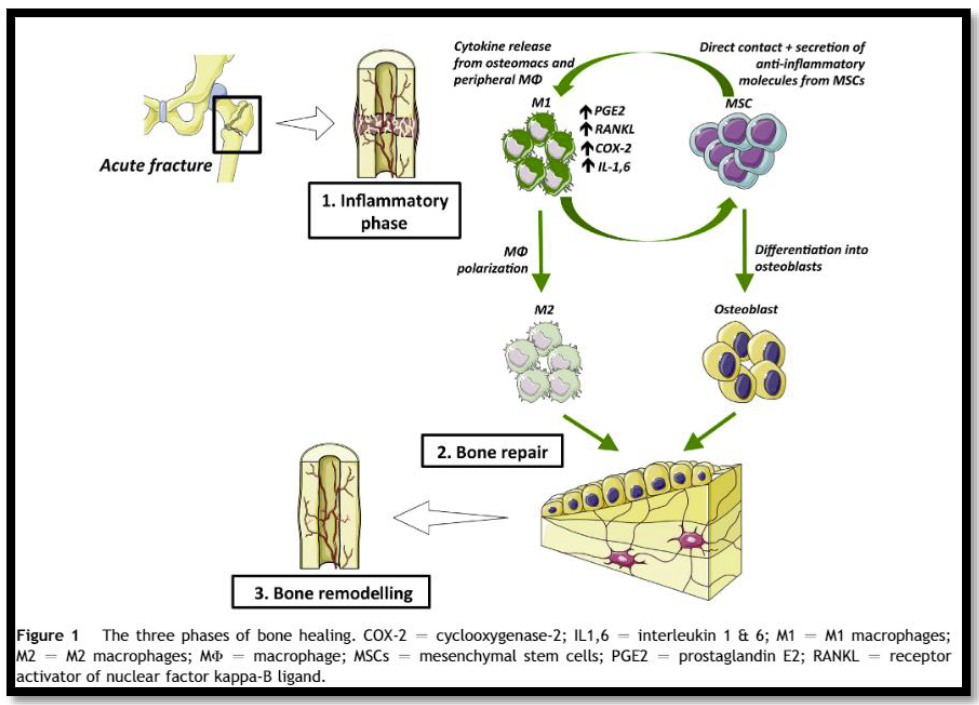

I’ve written so many posts about the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) it’s practically getting old. To summarize, some old animal studies suggested that using NSAIDs during fracture healing could impair the process. However, human studies were not so convincing.

Over the years, there has been quite a bit of conflicting evidence. This generally means the association between healing and NSAID use is weak. However, after this period of time, we should have become aware of a significant cause/effect relationship.

The Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma recently released a practice management guideline regarding the use of NSAIDs for the treatment of acute pain after orthopedic trauma. They used a standard methodology to identify and analyze published research. They focused on human studies specifically relating to this drug class’s use in fractures. The group ultimately identified 19 pertinent research papers for analysis, 10 of which were prospective, randomized studies.

Here are the three questions they asked, with their answers:

- Should NSAIDs be used in analgesic regimens for adult patients

(≥18 years old) with traumatic fracture versus routine analgesic

regimens that do not include NSAIDs to improve analgesia and

reduce opioid use without increases in non-union and acute kidney

injury rates? Although the quality of the studies for this question was low, EAST conditionally recommended using NSAIDs in pain control regimens. In the higher-quality studies in this group, there was no increased risk of non-union. - Should ketorolac be used in analgesic regimens for adult patients with traumatic fracture versus routine analgesic regimens that do not include ketorolac to improve analgesia and reduce opioid use without increasing non-union

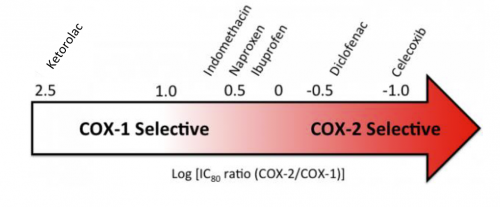

rates? This is the same question asked above, but with a specific drug rather than the class in general. The answer was basically the same. - Should selective NSAIDs (COX-2 inhibitors) be used in analgesic

regimens for adult patients (≥18 years old) with traumatic fracture versus routine analgesic regimens that include non-selective NSAIDs to improve analgesia and reduce opioid use without increasing non-union rates? COX-2 inhibitors are a subset of NSAIDs that are more selective in their action, blocking only the COX-2 receptor. Several years ago, there was a scandal regarding the COX-2 inhibitor rofecoxib (Vioxx). These selective drugs tended to have a higher incidence of cardiac complications. The manufacturer covered up this fact for several years, resulting in many unneeded deaths before it was removed from the market. The only COX-2 inhibitor available in the US is celecoxib. Only a few studies were performed using this drug during bone healing. There were not enough to make a recommendation.

Bottom line: EAST made conditional recommendations for using NSAIDs in general and ketorolac specifically in adults with fractures. “Conditional” only means that the authors did not have a consensus. Some voted to strongly recommend, and the remainder to conditionally recommend. There were no votes to recommend against their use.

The use of NSAIDs should complement a well-thought-out opioid regimen, which should also be combined with other non-narcotic medications and appropriate mobilization and therapy.

Reference: Efficacy and safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs (NSAIDs) for the treatment of acute pain after orthopedic trauma: a practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma and the Orthopedic Trauma Association. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2023 Feb 21;8(1):e001056. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2022-001056. PMID: 36844371; PMCID: PMC9945020.