The first EAST abstract I will discuss is the very first to be presented at the annual meeting. This is a prospective, observational studied that was carried out at the University of Pittsburgh. It looked at the association between repeated rapid thromboelastography (rTEG) results in pediatric patients and their death and disability after plasma administration. They specifically looked at the degree of fibrinolysis 30 minutes after maximum clot amplitude and tried to correlate this to mortality.

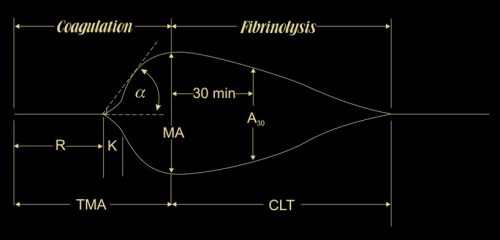

For those of you who need a refresher on TEG, the funny sunfish shape above shows the clot amplitude as it increases from nothing at the end of R, hits its maximum at TMA, then begins to lyse. The percent that has lysed at 30 mins (LY30%) gives an indication if the clot is dissolving too quickly (LY30% > 3%) or too slowly (LY30% < 0.8%).

The authors selected pediatric patients with TBI and performed an initial rTEG, then one every day afterward. They looked at correlations with transfusion of blood, plasma, and platelets.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 101 patients under age 18 were studied, with a median age of 8, median ISS of 25, and 47% with severe TBI (head AIS > 3)

- Overall mortality was 16%, with 45% having discharge disability

- On initial analysis, it appeared that transfusion of any product impeded fibrinolysis, but when controlling for the head injury, only plasma infusion correlated with this

- Increasing plasma infusion was associated with increasing shutdown of fibrinolysis

- The combination of severe TBI and plasma transfusion showed sustained fibrinolysis shutdown, and was associated with 75% mortality and 100% disability in the remaining survivors

- The authors conclude that transfusing plasma in pediatric patients with severe TBI may lead to poor outcomes, and that TEG should be used for guidance rather than INR values.

Bottom line: There is a lot that is not explained well in this abstract. It looks like an attempt at justification for using TEG in place of chasing INR in pediatric TBI patients. This may be a legitimate thing, but I can’t really come to any conclusions based on what has been printed in this abstract so far.

Here are some questions for the authors to consider before their presentation:

- There seem to be a lot of typos, especially with < and > signs in the methods.

- Disability is a vague term. What was it exactly? Was it related to TBI or the other injuries as well?

- These children also appear to have had other injuries, otherwise why would they need what looks like massive transfusion activation? Why did they need so much blood? Could that be the reason for their fibrinolysis changes and poor outcomes?

- I can see the value of the initial rTEG, and maybe one the next day. But why daily? What did you learn from the extra days of measurements? Would a pre- and post-resuscitation pair have been sufficient?

- Plasma is the focus of this abstract, but it does not describe how much plasma was given, or whether there was any departure from the usual acceptable ratios of PRBC to plasma administration.

- Big picture questions: Most importantly, why would you think that poor outcomes, which are the focus of this paper, are related to plasma administration? Why haven’t we noticed this correlation before? And how does daily TEG testing help you identify and/or avoid this? What questions raised here are you going to pursue?

Reference: EAST 2018 Podium paper #1.