Most stable patients with blunt trauma undergo CT scanning these days. Hopefully, it’s done thoughtfully to optimize the risk/benefit ratio using a well-designed imaging protocol. The majority of these torso imaging protocols call for the use of IV contrast. But as I’ve written before, this can pose risks, especially to the elderly and others who have some degree of renal impairment.

Unfortunately, I occasionally encounter scans done at other hospitals that omit the use of contrast. This usually hinders diagnosis significantly. And it’s usually not clear why this happened, so let’s think about it a bit.

The use of contrast in CT is designed to show blood, or things that are filled with lots of blood. Specifically, a great deal of detail about the blood vessels and solid organs is displayed.

Let’s break it down by type of scan:

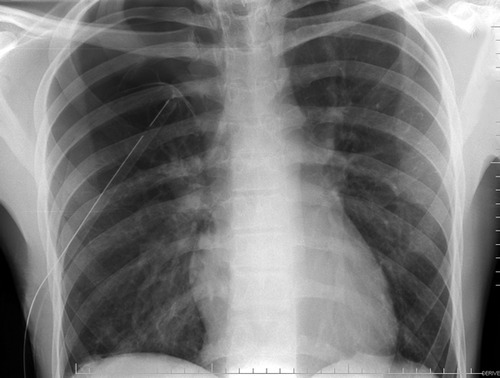

- Chest – we are really only interested in the aorta. The only way to reliably demonstrate an aortic injury is by using contrast. And this is one of those injuries that, if you miss it, the patient is very likely to die from it. Therefore, if you are ordering a chest CT properly, you must add contrast.

- Abdomen/pelvis – generally, we are looking for solid organ injury, potential mesenteric injuries, and extravasation of blood from organs or soft tissue. Once again, the only way to really see any of these is with contrast enhancement.

- Vascular – CT is replacing conventional angiography for the investigation of vascular injury in many cases. Obviously, this study is worthless without the contrast.

Bottom line: Pretty much any CT of the chest, blood vessels, or abdomen/pelvis must have IV contrast injected for accurate diagnosis. But what if your patient is old, or is known to have some degree of renal impairment? First, decide if you can wait until a point of care or standard creatinine measurement is done. If you can, use the result to do your own risk/benefit calculation. Is the injury you are worried about potentially life-threatening AND reasonably likely? Are there other less harmful ways to detect it? Then use them. And if you really do need the study in a patient with renal dysfunction, give the contrast, monitor the serum creatinine regularly, and do what you can to optimize and protect their renal function over the next several days.