In general, stab wounds to the anterior abdomen (like any penetrating injury to the area) demand further evaluation to make sure there are no significant injuries. In the old days, a stab to the abdomen mandated a trip to the operating room. Fortunately, we recognized that more than half of these operations led to negative explorations.

Nowadays we can be much more selective. Here is my approach to evaluating these patients.

First, are there any indications that the patient needs to go to the OR right now?Check the vital signs. If there is any hemodynamic instability, operate! Check the abdomen. If there is obvious peritonitis, or significant tenderness more distant from the actual stab site, off you go to the OR!

Next, after finishing all of the usual ATLS protocol it’s time to evaluate further.Several options exist:

- Observation – this is good for busy trauma centers that have lots of penetrating injury and busy ORs

- DPL – not used too much any more, but certainly is legitimate. I recommend that your RBC count threshold be reduced to 25,000 or 50,000

- Local wound exploration – this works in thinner people. Doing a LWE on an obese patient requires an incision that approaches the size of a small laparotomy. Might as well do it in the OR. Look for any violation of the anterior fascia.

- CT scan – the new kid on the block

To use CT, the patient must be stable (remember, they should be in the OR if otherwise) and have had a full ATLS evaluation. They should also not be terribly thin. Too little fat makes it difficult to gauge depth of the injury.

The entry site(s) should be marked with a small marker to minimize streak artifact. Resist the temptation to just scan the area around the stab itself. Do a full IV contrast (no GI needed) abdomen/pelvis scan.

Look closely for blood outlining the wound tract. If it reaches the anterior abdominal fascia, the exam is positive. You do not need to see specific injury to the muscle or abdominal viscera. Violation of the anterior fascia is an absolute indication to proceed to the OR. On occasion, the knife will not penetrating the posterior fascia, or penetrates but does not injury any organs. In these cases it is best to have operated and found nothing rather than delaying and increasing the risk of intra-abdominal complications or infections.

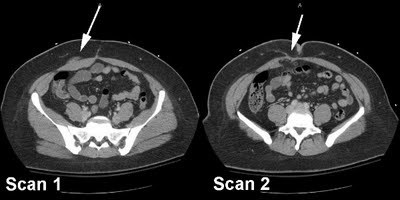

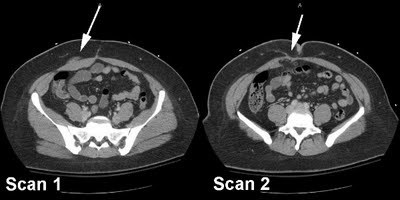

Scan 1 shows blood tracking to the anterior fascia, as well as an increase in size of the rectus muscle.

Scan 2 shows penetration of the posterior rectus sheath with intra-abdominal fat herniating into it. The transverse colon is only 2 cm away deep to it. Scan 1 alone is enough to prompt you to take the patient to the OR!