One of the potential complications of chest trauma causing hemothorax is the retained hemothorax. In most patients, retained blood slowly lyses and is reabsorbed. But a few do not, and scarring can occur that entraps the lung and interferes with pulmonary function. This can ultimately require a VATS or thoracotomy to resolve.

Several protocols have been developed to try to prevent a retained hemothorax. They include the use of lytics or an early VATS procedure. The group at the Medical College of Wisconsin performed a trial of thoracic cavity irrigation and compared the outcomes with patients who did not undergo irrigation. This was a single-center retrospective study performed over five years.

This appears to have been a common practice at this institution. Patients undergoing chest tube placement for hemothorax received irrigation of the chest cavity immediately after placement. The study excluded patients with chest tubes placed in other hospitals, tubes placed late (after 24 hours), or patients who had a chest procedure within 6 hours.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 370 patients were enrolled, and 225 (61%) received irrigation

- Demographics of the groups were the same, with the exception that the irrigation group contained more patients with penetrating injury and fewer patients with flail chest

- Use of irrigation was associated with significantly less incidence of retained hemothorax (10% vs 21%) or need for VATS (6% vs. 19%)

- Chest tube duration (4 vs 6 days) and hospital length of stay 8 vs 10 days) were also significantly shorter

The authors concluded that irrigation prevents retained hemothorax and decreases the need for surgical intervention.

Bottom line: Well, this was a new one for me. The only prior study I could find was published in 2022 by a group at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas. They irrigated 82 of 198 patients undergoing chest tube placement. They noted a decrease in hospital, ICU, and ventilator days.

This study looks at something far more practical: interruption of the development of a complication. Although still a relatively small and single-institution study, it was well done and could easily detect statistical significance.

The presenter should be prepared to discuss what impact the mechanism of injury (penetrating, flail chest) may have had on their results and the exact technique they used. How much fluid, what type, and how it was drained are all important questions to discuss.

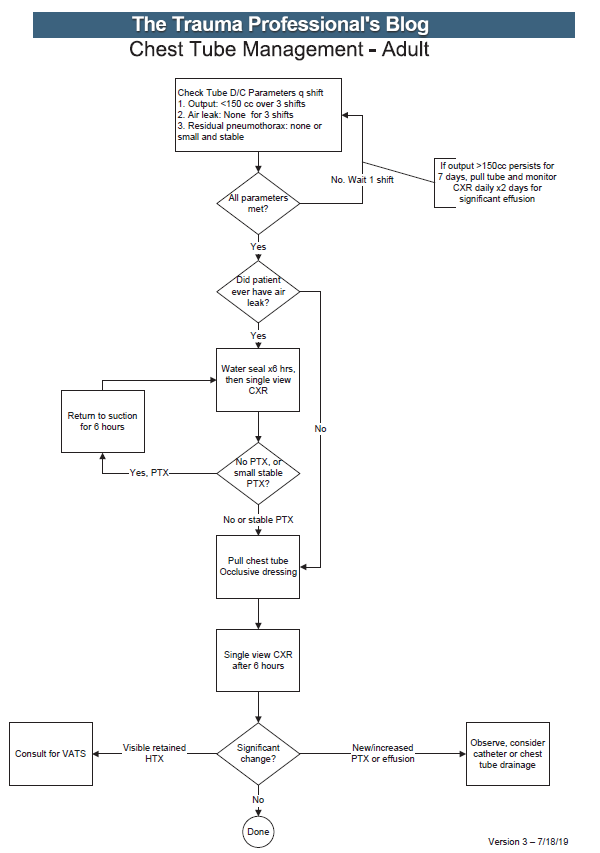

This is a fascinating abstract indeed. If the presentation answers the questions, centers should consider updating their chest tube management algorithms.

References:

- Thoracic cavity irrigation prevents retained hemothorax and decreases surgical intervention in trauma patients. EAST 2024, Podium paper #17.

- The Volume of Thoracic Irrigation Is Associated With Length of Stay in Patients With Traumatic Hemothorax. J Surg Res. 2022 Nov;279:62-71.