Performing a proper emergency thoracotomy is more difficult than you think. There are lots of details to consider, and the learning curve is steep. I’m going to split the process into three parts: getting in, dealing with the heart, and clamping the aorta.

The most important part of getting in is setting up your team. Someone has to be assigned to make sure the chemical and volume resuscitation part is carried out, because the person actually doing the thoracotomy is going to be busy. The most experienced person in the room will actually perform the procedure, or assist the physician who will be learning the procedure.

Next, protect yourself! This is a dangerous procedure. Emotions run high, and people are holding sharp objects. You don’t know where your patient has been or what is circulating in the little blood they may have left, so be careful and make sure you are wearing your personal protective equipment.

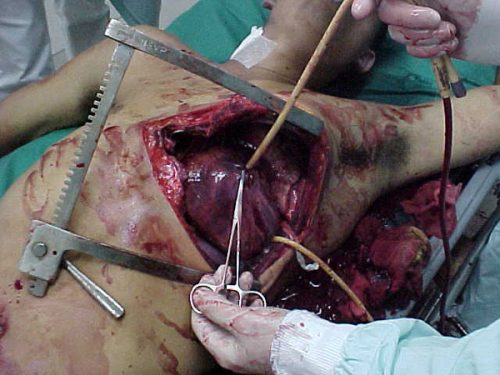

Finally, make the incision. This is usually placed along the fifth intercostal space, which is just under the nipple in men. Don’t start too close to the sternum, or you may cut the internal mammary artery. This won’t bleed until circulation is restarted, but it takes some effort to stop it later. Some people prefer a straight incision down toward the table, but I prefer a curved incision that follows the ribs, as illustrated.

Use the scalpel to incise skin, subcutaneous tissue and muscle. However, stop short of the pleura while you are incising the intercostal muscles. If you try to cut through the pleura with the knife, it’s alarmingly easy to injure the lung, or even the diaphragm. Use scissors instead.

Now it’s time to insert the retractor. I prefer to place it with the handle pointing down toward the feet so it doesn’t get jammed against the arm. This is not nice, polite thoracic surgery. You don’t open it a few turns and wait, trying to avoid rib fractures. Open it fast and all the way. Ribs will break, so be careful from this point onward so you don’t cut yourself on their sharp edges.

Related posts:

Tomorrow, I’ll describe what you need to do with the heart.

Image from my personal archive. Not treated at Regions Hospital.