Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) is one of the new, shiny toys in the trauma professional’s toy chest. Research papers on the topic are increasing exponentially, but human data was not even published until 2014! This is still a new device and we are trying to learn more about it.

The AAST set up an Aortic Occlusion for Resuscitation in Trauma and Acute Care (acronym is AORTA, ugh!) to help accumulate data for this not-often used technique. Hopefully, compiling comprehensive use and outcome data will speed our appreciation of the usefulness of this device.

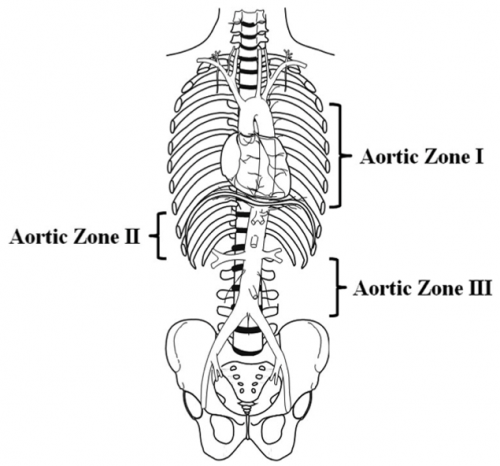

A multi-institutional trauma group massaged the AORTA registry to examine the potential benefits of using the technique in patients with pelvic fractures leading to severe blood loss. They specifically looked for patients with the balloon inflated in Zone 3 to decrease bleeding from below the aortic bifurcation. Here’s a diagram of the zones:

The authors identified a total of 109 patients pelvic fractures with bleeding from below the bifurcation.

Here are the factoids:

- The presenting patients arriving without CPR all had similar base deficit, lactate, and systolic BP. This shows us that the two groups are the same, but only for these three parameters. GCS was lower in the open aortic occlusion group. This could certainly contribute to a higher overall mortality in this group.

- Overall mortality was significantly lower in the REBOA group that included those arriving with CPR in progress (35% vs 80% for open occlusion)

- And when CPR patients were excluded, the mortality was significantly lower (33% vs 69%)

- One in ten patients undergoing REBOA suffered vascular access complications (vascular repair required, limb ischemia, distal embolization, or amputation)

- Complications among survivors were not different between the groups, nor were hospital or ICU lengths of stay or blood usage

The authors state that their data shows a “clear survival advantage” in those patients who undergo REBOA. Furthermore, this was accomplished without increasing systemic complications. They finally conclude that REBOA should be “strongly considered” for patients in shock due to pelvic trauma.

Not quite so fast here. There are several more factors in play than meet the eye.

First, a study that massages a REBOA database was generally constructed to see if REBOA is beneficial, especially in this time of rapid investigation. And it was performed by institutions who are using it regularly. This could introduce a significant degree of confirmation bias, since we all try to see what we already believe to be true (“REBOA is good”).

The authors are basing this “clear survival advantage” on overall mortality where only a few confounding factors have been controlled for. The GCS wild-card here is a perfect example. It could have considerably contributed to mortality in the open group, making it look bad. Who determined whether REBOA or open technique would be used, and why? This can have a major impact. What other factors might be present that are not even recorded in the database?

It is also stated that this increased survival was accomplished without increasing systemic complications. Perhaps, but that may be true of only the ones examined, or those recorded in the registry. Many may be missing. And what about the 10% incidence of limb issues in the REBOA group? This is a major problem and should not be glossed over. Although the patients that required a vascular repair were reported to do well, the others with ischemia or limb loss obviously did not.

Bottom line: Reading abstracts is like reading scientific papers, only more difficult because information is missing due to length limitations. Look at the title. Look at the conclusions. But don’t believe anything until you can understand every one of the results listed. And be sure to think about all the things that have to be left unsaid because of the size of the abstract!

Having said all that, I still have to be careful that this doesn’t trigger my own confirmation bias. My take is that REBOA is still an investigational device. We need further comprehensive data to make sure that survival and safety are properly balanced.

Here are some questions for the presenter and authors:

- The abstract describes the number of cases identified as 109; 84 REBOA and 25 open occlusions of the aorta. This seems to include patients undergoing CPR upon arrival, and these are excluded from some of the statistics. However, I can’t get the mortality percentages to match for the group that supposedly includes CPR patients. For example, the overall REBOA (includes CPR) mortality percentage is 35.17%. Multiplying this by 84 gives 29.5 patients. But multiplying the 33.33% mortality (CPR-excluded group) by 84 yields 28 patients. So are the 109 patients listed in the abstract the CPR-excluded group or not?

- The open aortic occlusion group had a lower GCS. Did you look at how this might have contributed to the higher observed mortality? Although numbers are already low, is there any way to match for this to clarify the picture?

- Do you have any information yet on longer term outcomes in the two groups? This will become very important as we come to balance raw survival with quality of life and complications.

Great abstract! I’m looking forward to the presentation, and hopefully more answers!

Reference: SURVIVAL BENEFIT FOR PELVIC TRAUMA PATIENTS UNDERGOING RESUSCITATIVE ENDOVASCULAR BALLOON OCCLUSION OF THE AORTA: RESULTS OF AAST, AORTIC OCCLUSION FOR RESUSCITATION IN TRAUMA AND ACUTE CARE SURGERY (AORTA) REGISTRY. AAST 2019 Oral Abstract #3.