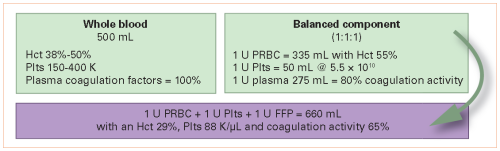

We’ve been using fractionated blood components in medicine, and trauma specifically, for over 50 years. So why doesn’t component therapy work so well for trauma? Refer to the following diagram. Although when mixed together the final unit of reconstituted blood looks like whole blood, it’s not. Everything about it is inferior.

Then why can’t we just switch back to whole blood? That’s what our trauma patients are losing, right? Unfortunately, it’s a little more complicated than that. The military has been able to use fresh warm whole blood donated by soldiers which has been stored for just a few hours. That is just not practical for civilian use. We need bankable blood for use when the need arises.

This ultimately means that we need to preserve the blood, and this requires a combination of preservatives to prevent clotting and keep the cellular components fresh, and refrigeration to avoid bacterial growth. This is not as simple as it sounds. Adding such a preservative to whole blood dilutes it by about 12%. And there are concerns that cooling it may have effects on platelet function. Recent data suggests that platelet function in cooled whole blood is preserved, but platelet longevity is decreased.

There are other issues with the use of whole blood as well. It contains a full complement of white blood cells, and this may be related to reports of venous thrombosis, respiratory distress, and even graft vs host disease. Unfortunately, removing the white cells (leukoreduction) also tends to remove the platelets, and there is little literature detailing the safety of this practice.

Another problem is the plasma component in whole blood. Universal donor (type O) whole blood may contain significant amounts of anti-A and anti-B antibodies. For these reasons, most blood banks limit the number of whole blood units transfused to a handful. A recent paper from OHSU in Portland details a massive transfusion in which 38 units were given to one patient. There was no transfusion reaction, but platelet counts dipped precipitously. All centers currently using whole blood utilize only low-titer anti-A and anti-B units.

So does whole blood work as expected in the civilian arena? The data is still incomplete, but the total transfusion volume appears to be decreased in patients without severe brain injury. With the increased interest and use of whole blood, it is imperative that more safety and efficacy studies are forthcoming.

Here are some tips on getting started with your own whole blood program:

- Develop a relationship with a supplier of whole blood. Hammer out the details of the exact product (product age, leukoreduction, titer levels, returnability if not used).

- Obtain approval from your hospital’s Transfusion Committee!

- Work with your blood bank to develop processes to ensure proper availability and accountability. What is the maximum number of units that can be used in a patient? When should units be returned to the general pool to ensure they are not wasted?

- Decide where whole blood will be available. Obviously, the blood bank will house the majority of the product. But should you have it in an ED refrigerator? On air or ground EMS units? These situations demand several extra layers of oversight and add greatly to complexity.

- Educate, educate, educate! Make sure everyone involved, in all departments, are familiar with your new MTP!

References:

- Whole blood for resuscitation in adult civilian trauma in 2017: a narrative review. Anesth Analg 127(1):157-162, 2018.

- Massive transfusion of low-titer cold-stored O-positive whole blood in a civilian trauma setting. Transfusion, Epub Dec 27, 2018.