The 35th Annual Scientific Assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) begins in only a month! I will be there, sitting in the front row listening to all the great presentations. As usual, I have selected some of the abstracts that I find most interesting and will be sharing my thoughts on them with you over the coming weeks.

Let’s start out with a paper about the massive transfusion protocol (MTP). Blood has always been a scarce resource. And now, thanks to COVID, it is becoming even more so. Every trauma professional reading this has likely been involved in a trauma resuscitation that has used dozens of units of blood and other products. Unfortunately, most of the patients who require this much do not survive.

How does one balance the rapid use of many, many units of blood products with the (un)likelihood of survival and the impact of having less blood for other patients in your hospital or future incoming trauma patients? In other words, when does the use of additional blood become futile? Until now, there have been no real answers to these questions.

The trauma group at George Washington University did a deep dive into the TQIP database seeking some guidance on this topic. They reviewed five years of data, targeting patients who received at least one unit of blood within four hours of arrival. Four-hour and 24-hour mortality was analyzed to determine the point at which additional blood products did not improve survival.

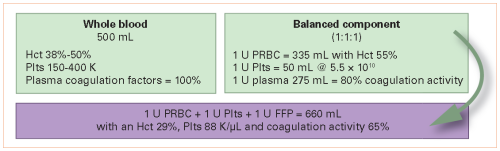

The authors looked at the data two ways. They analyzed the results for all comers, as well as for patients who received balanced resuscitation. Balanced was defined as a red cell to plasma ratio in the range of 1:1 to 2:1. Results were controlled as best as possible for age, sex, race, highest AIS in each body region, comorbidities, advanced directives, and the type of surgery performed to control bleeding.

Here are the factoids:

- Nearly 100,000 patient records were analyzed, and about 30,000 patients were found to have balanced resuscitation

- In the all-comers group, mortality plateaued after 41 units at 4 hours and 53 units at 24 hours

- In the balanced resuscitation patients, mortality plateaued at 40 units (4 hours) and 41 units (24 hours)

The authors concluded that this data should be used as markers for resuscitative timeouts to assess the plan of care.

My comments: This paper is very focused and provides some apparently straightforward results. However, it required some sophisticated statistical analysis to sift through the many variables that need to be controlled to obtain meaningful results. From reading the abstract, it appears that they did a good job of this.

I believe the lower number of units needed by 24 hours in the balanced resuscitation group demonstrates the benefit of getting the MTP ratios right. Non-balanced resuscitation is less efficient / effective and requires the use of more products to hit the mortality plateau.

This paper supports my opinion that a resuscitation timeout is a useful tool in helping us protect our valuable blood product resources and ensuring availability for as many patients in need as possible. What would this look like? Here are my thoughts:

- Assign one person to monitor the MTP process in real-time. This obviously cannot be the surgeon or a member of the anesthesia team. Or even the operating room crew, as everyone will be very busy. The best practice I’ve seen is to have a dedicated trauma nurse or APP in the ED/OR recording the process on a specialized form and directing which units to give to keep the resuscitation balanced.

- Call a timeout when the magic threshold is reached. This paper suggests that 40 is a good number.

- Require that another trauma surgeon come into the room and review the patient condition, operative findings, and progress thus far. The two surgeons should then come to a consensus regarding utility vs futility of further surgery. Based on that decision, the operative procedure either continues or stops.

- If the operation is to continue, then more timeouts should occur after a defined number of additional products are given.

Here are my questions for the authors / presenter:

- The statistical analysis required is fairly advanced. Please explain in simple language why the specific regression analysis with bootstrapping was selected.

- How do you envision applying the thresholds discovered in your paper?

This is an exciting paper and provides important information about the MTP process. I’m looking forward to hearing it in person!

Reference: CRESTING MORTALITY: DEFINING A PLATEAU IN ONGOING MASSIVE TRANSFUSION, EAST 25th ASA, oral abstract #14.