More and more people are taking antiplatelet or antithrombotic agents for a variety of medical conditions. One of the dreaded side effects of these medications is undesirable bleeding, particularly after injury. This is especially true if the bleeding occurs inside the skull after any kind of head trauma.

Which agents, if any, lead to worse outcomes? The literature has been a bit inconsistent over the past 10 years. A group from HCA Healthcare reviewed the trauma registries from 90 hospitals, which I presume are in the HCA system. They included patients patients who suffered a ground level fall and were 65 years or older. They excluded those who had a significant injury to regions other than the head.

Here are the factoids:

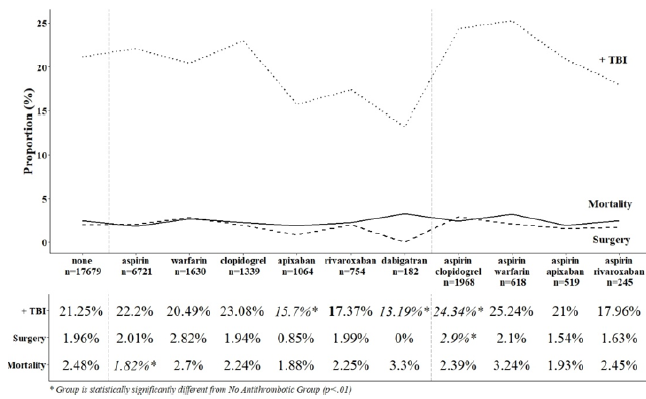

- Over, 33,000 patient records were reviewed, with an average age of 81

- Nearly half were on single or multiple anti-thrombotic therapy (!)

- The proportion of patients sustaining a “TBI” was roughly the same (21%) whether they were not on anti-thrombotic therapy or not

- Apixaban and rivaroxiban were associated with lower rates of “TBI” (13-16%)

- Clopidogrel was associated with a higher “TBI” rate (23%)

- Patients requiring brain surgery were more common in patients taking aspirin plus clopidogrel (2.9%) vs all the others (2%) and this was statistically significant

- None of the treatment regimens were associated with higher mortality (roughly 2-3%)

The authors conclude that anti-thrombotic use in the elderly who suffer a ground level fall are not at risk for increased mortality and that they may have negligible impact on management.

My comments: The one thing that makes this abstract difficult to read is their use of the term TBI, which is why I put it in quotes above. I think that the authors are conflating this acronym with intracranial hemorrhage. It’s a bit confusing, because I think of TBI as a term that means the head was struck and either left a physical mark (bump on the outside or blood on the inside) or there was known or suspected loss of consciousness. They are apparently using it to describe intracranial bleeding seen on CT.

And because this is a registry study, many of the patient-specific outcome details cannot be analyzed. Mortality and operative rates are very crude outcomes. What about some of the softer ones? Although the average GCS was stated to be 14.5, it would be interesting to know how many of these patients were able to return to their previous living situation, and how many were significantly impaired even though they didn’t die or need an operation.

Here are my questions for the presenter and authors:

- How do you define a TBI in this study? Could it be just a concussion? Does it require some type of blood in the head? Assuming that there are lots of TBIs that occur without intracranial bleeding, including such patients in your analyses will skew the data toward lower incidence and will dilute out the patients with hemorrhage.

- What was the length of your study? If it includes data that is older than six years or so, it may under-represent the use of some of the direct oral anticoagulant drugs (DOACs).

- Are half of your elderly falls patients really on anti-thrombotic therapy? This is a shocking number, and seems to be high in my experience. Since your study was distributed across a large number of hospitals, it brings up the question of whether so many of our elders really need this medication.

- Do you have any sense for how your various subgroups fared in terms of their discharge disposition? You conclude that the use of anti-thrombotic agents isn’t so bad, really. At least when it comes to needing brain surgery or dying. But are there other cognitive issues that are common that might encourage trauma professionals to continue to look at these drugs with a wary eye?

This is important work, and I am anticipating a great discussion after your presentation.

Reference: Antiplatelet and antiplatelet agents, alone and in combination, have minimal impact on traumatic brain injury (TBI) incidence, need for surgery, and mortality in ground level falls (GLFs): a multi-institutional analysis of 33,710 patients. AAST 2020 Oral Abstract # 7.