Here’s another abstract on trauma center / system finance. Trauma centers are part of the safety net in the healthcare systems of many countries. The way they are funded varies tremendously. In the US, health insurance pays most of the bill for patient care. Unfortunately, not all patients are covered, so there is financial risk to the center based on how many underpaying patients present for care.

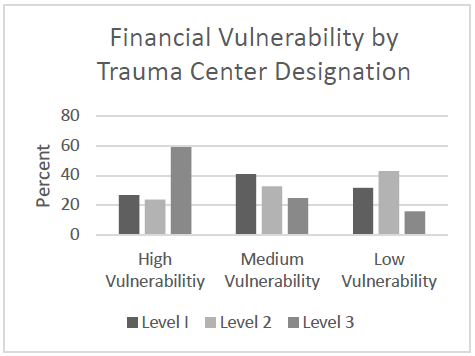

The group at Scripps Mercy in San Diego performed a financial health analysis of all ACS-verified trauma centers in the US. They applied a Financial Vulnerability Score metric (FVS), although I could not locate anything on this via an internet search. They analyzed the RAND Hospital Financial Database, which is based on information obtained from the CMS Healthcare Cost Report Information System. Using this data they calculated the FVS for each center. They sub-grouped the hospitals into high, medium, and low vulnerability and compared them.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 617 trauma centers were identified and analyzed: 194 Level I, 278 Level II, and 145 Level III

- Level III trauma centers made up 59% of the high financial risk centers

- The majority of Level I and II centers were in the middle or low risk categories

- Characteristics of high risk centers were lower number of beds, negative operating margin, and less cash on hand

- Low risk centers had greater asset to liability ratios, lower outpatient shares, and 3x less uncompensated care

- The largest proportion of HFR hospitals were in New England and East North Central regions

- Non-teaching centers had significantly higher financial risk than teaching hospitals (46% vs 29%)

The authors concluded that about 25% of Level I and II trauma centers are at high financial risk and that factors such as payor mix and outpatient status should be targeted to reduce this risk.

Bottom line: This is a fascinating abstract but leaves a lot to the imagination. The databases used have not been used in previous papers, and the information contained in them is proprietary. The FVS is also new and I have not been able to obtain any details.

Nevertheless, if the data and analysis are sound it may provide some new information to trauma centers and perhaps some insight on what factors to address to lessen their financial vulnerability. This is a lot of ifs. Hopefully the authors will enlighten us during the presentation so we can appreciate the real world value of the analysis.

Here are my questions and comments for the authors/presenter:

- Please explain both the dataset used and the new FVS metric. Most readers and listeners are unfamiliar. We need to see how the data and analysis apply to trauma center financials and how the FVS has been validated.

- How can the vulnerability factors be addressed? Payor mix is based on patient coverage and their socioeconomic status. It would seem to be difficult to manipulate by the trauma center. Outpatient vs inpatient status is also difficult to change and not fall afoul of CMS rules. What were other factors that were identified that could help centers reduce their financial vulnerability?

This could be an interesting abstract, but there was not enough room in the abstract to reveal all the details. Hopefully all will become obvious during the presentation.

Reference: FINANCIAL VULNERABILITY OF TRAUMA CENTERS: A NATIONAL ANALYSIS, Plenary paper #41, AAST 2022.