Like so many things in trauma, there are two camps when it comes to repeat CT scan after solid organ injury: the believers vs the non-believers. In my experience, a minority of US trauma centers incorporate this repeat CT study in their practice guidelines.

Yet the question keeps coming up in the literature. Earlier this year, I reviewed a paper from the University of Cincinnati from a group of believers. I was not very kind, and you can read the review here. The biggest problem with most believer papers is that they cite very old literature that overstates the incidence of delayed hemorrhage. They then use this to justify an extra CT scan to find more of these “dangerous” pseudoaneurysms. Unfortunately, those old papers are just not very good and many overstate the problem.

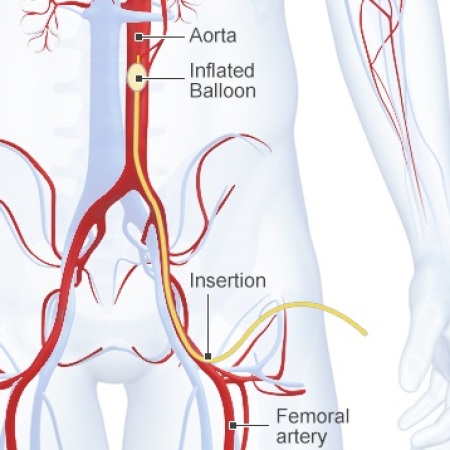

So let’s look at this year’s abstract from the LAC+USC group. They open by stating that the natural history is unclear but that “risk for spontaneous rupture and exsanguination exist.” The authors sought to further define the utility of using a delayed CT angiogram (dCTA) in diagnosing and triggering intervention after high-grade blunt solid organ injury.

They performed a retrospective study of all patients arriving at their Level I center over a nearly five year period with a Grade 3 or higher injury to liver, spleen, or kidney. They excluded the young, patients transferred in, early deaths, and patients who underwent immediate operation on their spleen or kidney. The primary outcome was intervention triggered by the dCTA.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 349 patients with 395 high grade solid organ injuries were analyzed (42% liver, 30% spleen, 28% kidney)

- Median injury grade for each organ was 3

- Initial management was “typically” nonoperative or angioembolization (liver 83%, spleen 95%, kidney 89%)

- Delayed CT angiogram was typically performed on day 4 and identified a lesion in 16 spleen, 10 liver, and 6 renal injuries

- The dCTA prompted an intervention in 12 spleen, 8 liver, and 5 kidney injuries

The authors conclude that delayed CTA identified a significant number of vascular lesions requiring endovascular or surgical intervention. They recommend further examination and consideration of universal screening to avoid missing these pesky pseudoaneurysms.

Bottom line: Once again, we have a paper that conflates finding a pseudoaneurysm with the need to get rid of it. Granted, I was always taught that pseudoaneurysms (in adults) found on initial CT required an intervention. In the old days of “delayed splenic rupture” a pseudoaneurysm was the likely culprit.

But the majority of centers do not go looking for pseudoaneurysms days later. And there are precious few patients coming back with delayed hemorrhage after discharge. So what gives?

Could it be that there is a difference between a “fresh” pseudoaneurysm and a “delayed” one? Perhaps the fresh ones portend a real risk of bleeding, but delayed ones are just a normal part of the healing process and rarely bleed? We just don’t know for sure.

This paper shows that if you look for a delayed pseudoaneurysm you will find them. And at this center, if you find them you will be compelled to angioembolize or even operate on them. Yet we really don’t know if that is necessary. It certainly adds to length of stay and hospital charges.

My take is that we desperately need a broad tally of patients discharged with a liver or spleen injury who return within a few weeks for bleeding complications. I would exclude kidneys because they act so differently. And I would not look at all returns because most liver injury readmissions are for bile problems. Just focus on readmissions for bleeding. Once we see what the real incidence is, we can decide whether these pseudoaneurysms are a problem significant enough to pursue with delayed scans, etc.

Here are my questions for the authors and presenter:

- What is your assessment of the incidence of delayed rupture and exsanguination? Have you read through the old papers in detail to assure yourselves that they are actually correct?

- Do you hold patients in the hospital for their delayed CT angiogram? The studies were typically performed on days 3-7. Do you really keep your solid organ injured patients in the hospital that long? At our center, a grade 3 injury could be discharged home in two days!

- How do you decide to take a patient to interventional radiology or the OR after the delayed CT? Is it an unwritten rule? It seemed like most, but not all, had some type of intervention. A (very) few had the lesion but nothing was done. Please explain the difference.

This is an interesting paper just because of the intuitive leap it makes from pseudoaneurysm to intervention. I’m anticipating your presentation so I can hear all the details.

Reference: PSEUDOANEURYSMS AFTER HIGH GRADE BLUNT SOLID ORGAN INJURY AND THE UTILITY OF DELAYED CT ANGIOGRAPHY. Plenary paper #34, AAST 2022.