A bucket handle injury is a type of mesenteric injury of the intestine. The intestine itself separates from the mesentery, leaving a devascularized segment of bowel that looks like the handle on a bucket (get it?).

These injuries can occur after blunt trauma to the abdomen. The force required is rather extreme, so the usual mechanism is motor vehicle crash. In theory, it could occur after a fall from a significant height, and I have seen one case from a wood fragment that was hurled at the abdomen by a malfunctioning lathe.

The mechanics of this injury are related to fixed vs mobile structures in the abdomen. Injuries tend to occur adjacent to areas of the intestine that are fixed, such as the cecum, ligament of Treitz, colonic flexures and rectum. During sudden deceleration, portions of the intestine adjacent to these areas continue to move, pulling on the nearby attachments. This causes the intestine itself to pull off of its mesentery.

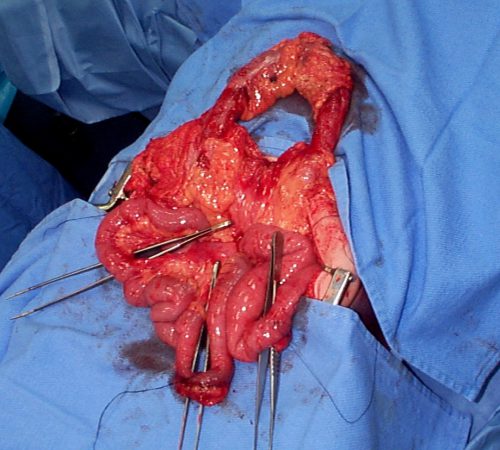

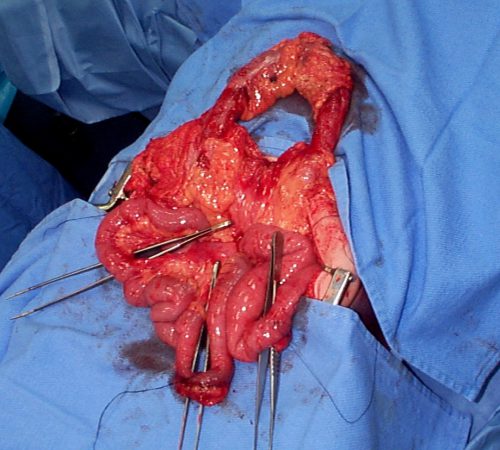

Source: personal archive. Not treated at Regions Hospital

The picture above shows multiple bucket handle injuries in one patient. There are 3 injuries in the small bowel, and one involving the entire transverse colon. Note the obviously devascularized segment at the bottom center of the photo.

The terminal ileum is the most common site for bucket handle tears. Proximal jejunum, transverse colon, and sigmoid colon are other possible areas. In my experience, the driver is more likely to sustain an injury to the terminal ileum, and the front passenger to the sigmoid. I think this is due to the location of the buckle, but it’s just my own observation.

Always think about the possibility of this injury in patients with very high speed deceleration. Seat belt marks have a particularly high association with this injury. If your patient has an abnormal exam in the right lower quadrant, or if the CT shows unusual changes there (“dirty” mesenteric fat, thickened bowel wall, extravasation), I recommend a trip to the OR. In these cases, an injury will nearly always be present. And since the affected intestine may take a few days to die and leak, look for an unexplained rise in WBC beginning on hospital day 2.

Related posts: