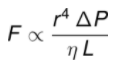

Hypocalcemia has long been known to exacerbate coagulopathy. Calcium is involved at several points in the coagulation cascade. Once serum levels drop below about 0.25 mmol/L (normal value 1.2-1.4 mmol/L) thrombin generation and clot formation cease. Although levels this low are probably rare, anything between this low and the normal level can significantly lower clot strength.

Trauma patients are more likely to have bleeding issues than most, and trauma professionals do their best to avoid coagulopathy. Unfortunately, the products we use to replace shed blood are preserved with citrate, which binds calcium. Given in even modest to large quantities, transfusion itself can lead to hypocalcemia.

Most blood transfused in the US has been broken down into separate components (packed cells (PRBC), plasma, platelets) and the effect on calcium levels is well known. The trauma group at Oregon Health Sciences University studied the impact on calcium of whole blood transfusions.

They performed a retrospective review of data collected prospectively over a 2.5 year period on patients receiving whole blood. This included the number of transfusions, ionized calcium levels, and calcium replacements administered. Patients were divided into two groups, those who received whole blood only and those who were given whole blood and component therapy. Outcomes evaluated were ionized calcium levels, hypocalcemia correction, and death.

Here are the factoids:

- During the study period, 335 patients received whole blood, but only 67% met inclusion criteria

- About half (103) received a median of 2 units of whole blood (only!)

- The authors do not state how many component units the whole blood plus component therapy group received

- There was no difference in calcium levels based on average ISS in the two groups, although ISS does not differentiate injuries that bleed very well

- Hypocalcemia occurred in only 4% of whole blood patients vs 15% of whole blood + components, which was significant

- Hypocalcemia within the first hour was significantly associated with death in the first 24 hours and 30 days, although the standard deviation or SEM of this value was large

- Whole blood only patients received less calcium replacement, and failure to correct was associated with 24 hour mortality

- Median time to death in patients that “failed to correct” was 7.5 hours after admission

The authors conclude that hypocalcemia rarely occurs in whole blood only resuscitation, and that adding components increases its incidence and overall mortality. They state that aggressive calcium supplementation should be prioritized if component therapy is used.

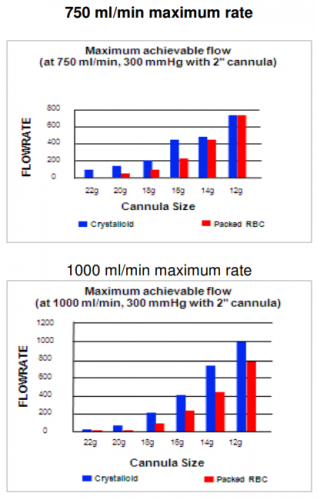

Bottom line: There’s a lot to “unpack” here! Packed red cells are preserved with 3g of citrate per unit, whereas whole blood units contain only half that amount (1.66g to be exact). One would expect that one unit of packed cells would have twice the anticoagulant effect as a unit of whole blood.

This study is a blended model, where every patient got some whole blood, but some got components as well. Why? Is there a blood refrigerator in the ED stocked with whole blood, and when it is exhausted there is a switch to components? This model makes it more difficult to tease out the impact of the components given. Perhaps it could be done by matching patients with a given amount of whole blood. That is, comparing patients with 3 whole blood with those who received 3 whole blood + 2 PRBC.

There was no room in the abstract to explain why one third of patients were excluded from the study. This needs to be provided to ensure that the remaining two thirds are representative and can legitimately be analyzed.

The number of units of whole blood per patient was low, with a median of two units given. Is it surprising that these patients did better than ones who received many more? Remember, from a citrate anticoagulant perspective, hanging two units of whole blood is the same as giving just one unit of PRBC.

This abstract raises a lot of questions, and the most important ones deal with how it was designed and the exact numbers of product given. Only then can we be confident that the rest of the associations described are significant.

Here are my questions for the authors and presenter:

- Why did you choose the whole blood vs whole blood + components for your study? Wouldn’t it have been cleaner to do whole blood only vs components only? Perhaps all of your patients get whole blood? It seems like this might make the results more difficult to tease out.

- How is whole blood made available for your trauma patients, and did this have an impact on your study? Do you have a limited number beyond which component therapy is used?

- What were the inclusion criteria? These were not stated in the abstract, but a third of patients were excluded from the study based on them.

- Could excluding a third of patients have skewed your results, and how?

- How many component units were given along with the whole blood in the combination group? This was not provided in the abstract and will have a major impact on outcomes if the median total product numbers are significantly higher.

- What does “failed to correct” mean? Were the patients not responding to large amounts of administered calcium, or were they not receiving large amounts of it?

I am very interested in the fine details in this abstract and will be listening intently to the presentation!

Reference: WHOLE BLOOD RESUSCITATION IN TRAUMA REGULATES CALCIUM HOMEOSTASIS AND MINIMIZES SEVERE HYPOCALCEMIA SEEN WITH COMPONENT THERAPY. EAST 35th ASA, oral abstract #6.