Yesterday, I reviewed a small case report that was published a couple of years ago on lytics for treatment of retained hemothorax. But surely, there must be something better, right?

After digging around, I did find a paper from 2007 that prospectively looked at protocolized management of retained hemothorax, and its aftermath. It was carried out at a busy Level I trauma center over a 16 month period.

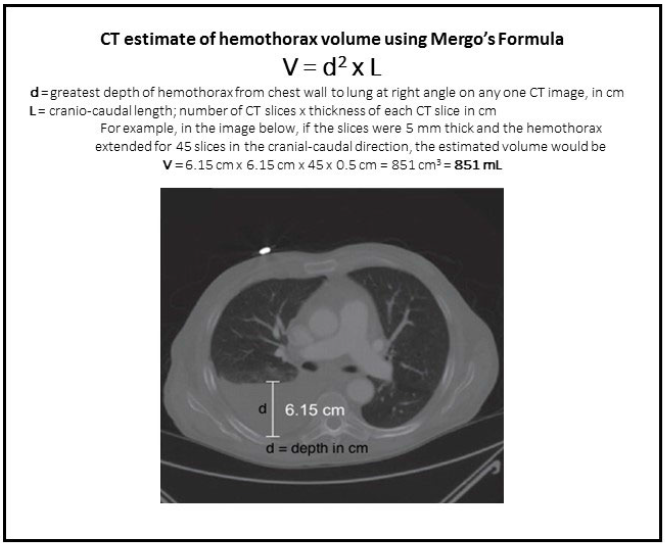

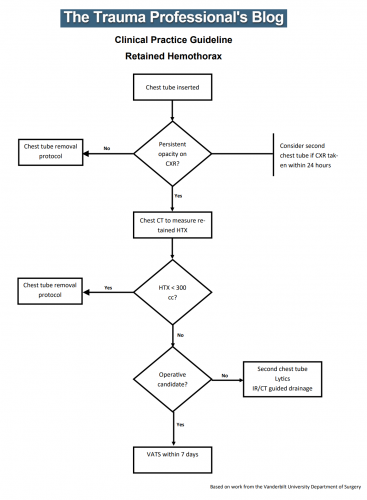

All patients with a hemothorax treated with chest tube received daily chest x-rays. Those with significant opacification on day 3 underwent CT scan of the chest. If more than 300 cc of retained blood was present, the patient received streptokinase or urokinase (surgeon preference and drug availability) daily, and rolled around in bed for 4 hours to attempt to distribute it. The chest tube was then unclamped and allowed to drain. This was repeated for 3 days, and if there was still opacification, a repeat CT was obtained. If the volume was still greater than 300 cc, the cycle was repeated for the next 3 days. If the opacification cleared at any point, or the repeat CT showed less than 300 cc, the protocol was stopped and the chest tube removed. If the chest was still opacified after 6 days, VATS was offered.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 203 patients with hemothorax were admitted during the study period and 25 (12%) developed a retained hemothorax

- While a few had treatment start within 4 days, the majority did not receive lytics until day 9 (range 3 –30 days!)

- The average length of time in hospital after start of lytics was 7 days, leading to a total length of stay of 18 days

- 92% of patients had “effective” evacuation of their retained hemothorax, although 1 had VATS anyway which found only 100 cc of fluid

- 16 patients had “complete” evacuation, and 5 had “partial” evacuation

- There were no hemorrhagic complications, but one third of patients reported significant pain with drug administration

Bottom line: Sounds good, right? The drug seems reasonably effective, although lengths of stay are relatively long. However, streptokinase and urokinase are no longer available in the US, having been replaced with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA). This paper does a cost analysis of lytics vs VATS and found that the former treatment cost about $15000 (drug + hospital stay) vs $34000 for VATS. However, a big part of this was that the drug only cost about $75 per dose. tPA is much more expensive.

So once again, small series, longer lengths of stay, but at least nicely done. Unfortunately, the drug choice is no longer available so use of tPA tilts the balance away from lytics.

Reference: Intrapleural Thrombolysis for the Management of Undrained Traumatic Hemothorax: A Prospective Observational Study. J Trauma 62(5):1175-1179, 2007.