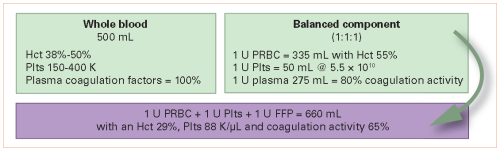

Here’s another abstract with a promising title that suffers from low subject numbers. Whole blood is the new darling of trauma resuscitation. Assembling a unit of whole blood from the components it was broken down into produces an inferior product from the standpoint of resuscitation.

It makes sense from a coagulation standpoint, but there are a few pesky issues that need to be considered, such as antibody titers. So I understand the enthusiasm to get some papers out there that describe the value of it.

A group in the Czech Republic performed a prospective study that assigned patients to receive scene resuscitation with either one unit of packed cells plus one unit of plasma, or two units of low titer group O whole blood. They had a host of primary outcomes, including feasibility, 24-hour and 30-day mortality, 24-hour blood use and fluid balance, and initial INR. They compared the two groups to matched cohort controls from a trauma registry. The study was performed over a three year period.

Here are the factoids:

- Three groups of about 50 patients each were enrolled

- There was no difference in 24-hour mortality, but the authors claimed that the 30-day mortality was “better.” However, the numbers were not statistically significant.

- They found a statistically significant decrease in 24-hour transfusion volume of about 500cc, which is not clinically significant

- Similarly, there was an increase in fluid balance of about 2L

- They also found a “significant” decrease in INR from 1.17 to 1.10, which is also not clinically significant

- There were no transfusion reactions

The authors concluded that whole blood was safe to give at the scene and that there were improvements in the measured parameters.

Bottom line: Sorry, but the abstract does not really support the title. This study is woefully small, and confusing to read. The purpose of the registry control cohort was not clear, and the extra results further muddied the picture. The statistical analyses were not included, and I am skeptical that they fully support the conclusions. There is just no statistical power to achieve significance with the number of subjects in this study. And many of the differences, even if they were statistically significant, were not clinically significant.

I don’t want to be a downer here. I do believe that whole blood is a good thing. Unfortunately, the whole blood in this study could have been better used doing a much bigger, multicenter study to truly show us the benefits.

Reference: Whole blood on the scene of injury improves clinical outcome of the bleeding trauma patient. AAST 2023, Plenary paper #28.