Urgent and emergent intubation is challenging enough, but what if your patient is sporting some type of tongue piercing? Does it make a difference? Do you need to do anything differently?

Obviously, the jewelry may physically impede the process of intubating the patient, impairing visualization of structures or getting in the way of inserting the tube. It can also cause complications later down the road, such as pressure necrosis from the tube coming into contact with it.

The anesthesia literature recommends removing all oral jewelry prior to elective intubation, or declining to do the case if the patient refuses. Unfortunately, trauma professionals do not have that option when the patient needs an emergency airway.

Here are some pointers for dealing with oral jewlry:

- Is the item going to impede insertion of the airway? Is it large, or obstructing the usual tube pathway? If so, remove it quickly (see below).

- Sweep the tongue well to the side during tube insertion to avoid the jewelry. You may need an assistant to grasp it with gauze to keep it out of the way.

- Once the airway is secured, remove the item. This takes two people! The ET tube should be moved to the side, and one person will grasp the tongue with a gauze pad and extend it. The other person can then grasp the jewelry with gloved fingers, and unscrew the ball on one side. It can then be removed and saved in an envelope.

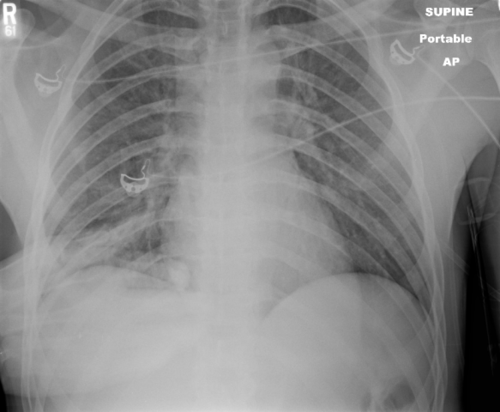

Note: both hands must always be in contact with the jewelry at all times! It is slippery, and if the pieces are not controlled, this can happen!