Most trauma programs can be divided into two types: those that believe in tranexamic acid (TXA) and those that don’t. I won’t get into the details of the CRASH-2 study here. But those centers that don’t believe usually give one of two reasons: they don’t think it works or they think the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is too high.

EAST put together a multi-institutional trial to see if there was an association between TXA administration and subsequent VTE. The results are being reported as one of the paper presentations at the meeting this week. A retrospective study of the experience of 15 trauma centers was organized. A power analysis was preformed in advance, which showed that at least 830 patients were needed to detect a positive result.

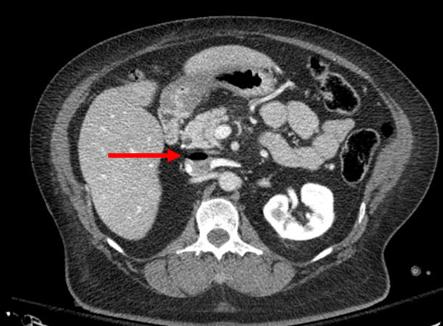

Adult patients who received more than 5 units of blood during the first 24 hours were included. There were a lot of exclusionary criteria. They included death within 24 hours, pregnancy, pre-injury use of anticoagulants, interhospital transfer, TXA administration after 3 hours, and asymptomatic patients that had duplex VTE surveillance (huh?). The primary outcome studied was incidence of VTE, and secondary outcomes were MI, stroke, length of stay, and death.

Here are the factoids:

- There were 1,333 eligible patients identified, and 887 (67%) received TXA

- Females were significantly (over 2x) more likely to receive TXA (46% vs 19%)

- 80% of patients given TXA received VTE prophylaxis, whereas only 60% of those who did not receive TXA got prophylaxis (also significant)

- TXA patients had a statistically significantly higher ISS (27) compared to non-TXA patients (25) but this is not clinically significant

- Mortality in the TXA group was significantly lower (17% vs 34%)

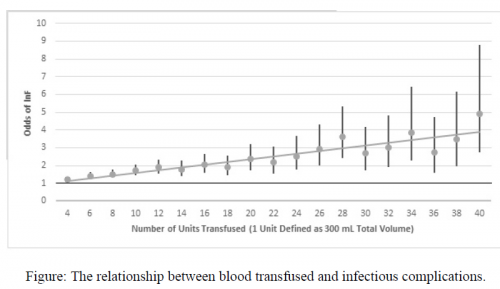

- The number of units of blood, plasma, and platelets transfused were significantly lower in the TXA group

- VTE rate appeared lower in the TXA group, but once multivariate analysis was applied, there was no difference

The group concluded that there was no association between TXA and VTE, but that it was linked to decreased mortality and transfusion need.

My comment: This was a study done the way they are supposed to be! Know your objectives and study outcomes up front. Figure out how many patients are needed to tease out any differences. And use understandable statistics to do so.

But, of course, it’s not perfect. No retrospective study is. Nor is any multi-institutional trial. There are lots of little variations and biases that can creep in. But the larger than required sample size helps with reducing the noise from these issues.

Basically, we have a decent study that shows that the clinical end points that we usually strive for are significantly improved in patients who have TXA administered. We don’t know why, we just know that it’s a pretty good association.

This study shows that the usual reasons given for not using TXA don’t appear to hold true. So hopefully it will convert a few of the TXA non-believers out there. I’m excited to hear more details during the presentation at the meeting.

Reference: Association of TXA with venous thromboembolism in bleeding trauma patients: an EAST multicenter study. EAST Annual Assembly, Paper #13, 2020.