A few days ago, I wrote about a paper that seemed to suggest that using a smaller chest tube (28-32 Fr) vs larger ones (36-40 Fr). The results suggested that their function was very similar. I emphasized that I thought the result was intriguing, because I’m of the opinion that bigger is better for getting clotted blood out. However, I am amenable to changing my mind based on newer, better data.

But I did caution readers that I would like to see more data. One study should never change your practice! Then I see a lot of chatter on Twitter about another study from 2016 that looks at even smaller tubes, with people saying they will now switch to pigtail catheters (12 Fr)!!

First, not a logical progression of thinking there. And second, let’s take an actual look at the paper. It’s from an emergency medicine group in Fukui, Japan, which retrospectively reviewed their 7 year experience with using a small (20-22 Fr) vs large (28 Fr) tubes. They identified a total of 124 chest tube insertions to compare, 68 small and 56 large.

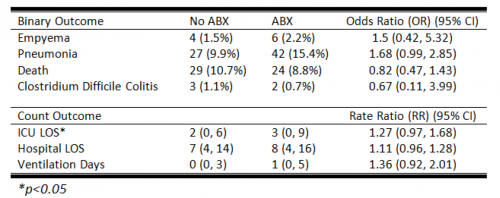

Now let’s look at the factoids:

- Demographics, mechanism, and ISS were the same between groups

- Duration of insertion and initial drainage were also the same between groups

- Complication rates were similar, with 1 empyema and 2 retained hemothoraces in each group

- Additional tubes were place in 2 patients with small tubes vs 4 with large tubes

- Thoracotomy was performed in 2 patients with small tubes vs 1 with a large tube

Based on all of this, the authors concluded that there was no difference in drainage efficacy, complications, or need for additional invasive procedures.

Wait a minute!! Again, if you only read the abstract, you might be led to start using ever smaller chest tubes. But read the entire paper! There are many problems with this paper, including:

- It’s a very small, retrospective review. This automatically means that the statistical power is suspect.

- Why did they only document 124 insertions over 7 years?? That’s about one every 3 weeks! Either a lot of data are missing or they are not very busy. But Fukui Prefectural Hospital has over 1000 beds! So it’s the former, not the latter.

- The retrospective nature means it is not possible to determine why a particular tube size was chosen. Roll of the dice? This fact alone introduces a huge potential for selection bias. Was a smaller tube selected because the hemothorax looked smaller? Probably! The fact that 4 patients with larger tubes had another one placed suggests that they were being used for larger collections. And patients with higher ISS tended to get bigger tubes.

Bottom line: Don’t change your practice based on this paper. And certainly don’t choose to use even smaller pigtails. And of course, always critically read any paper that you like to make sure you are not cherry picking the ones you choose to believe. IMHO, it’s still best to use big (36 Fr) or bigger (40 Fr).

Reference: Small tube thoracostomy (20-22 Fr) in emergent management of chest trauma. Injury 48:1884-1887, 2016.