This is an old question: what is the best way to insert a chest tube? There are several techniques available to us:

- Blunt dissection and insertion

- Trocar with a blunt tip (plastic stylet)

- Trocar with a sharp tip (metal stylet)

- Seldinger technique for small tubes

Typically, when there are multiple ways to do a thing, then there is no clear choice as to which is better. It then becomes a personal choice, or one driven by the financial considerations of the equipment used, and demonstrates the need for a practice guideline.

There are very few good papers out there that critically compare any of these techniques. Today, I’ll review one cadaver study and tomorrow I’ll tackle one “best evidence” paper that attempt to answer it.

A group in Vienna, Austria performed a cadaver study comparing the use of the two types of trocar tubes:

The top tube is the sharp trocar type, the bottom is the blunt trocar.

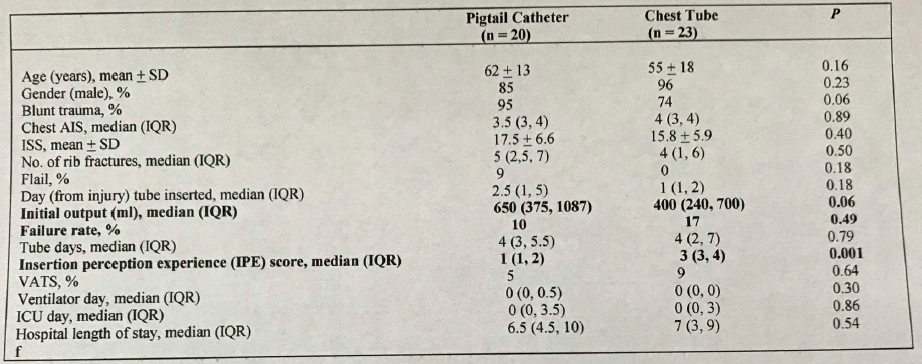

The study engaged twenty emergency medicine residents who had little, if any, experience placing chest tubes. Each placed 10 chest tubes (5 of each type) in fresh cadavers after undergoing a one-hour standardized lecture on anatomy, technique, and complications. The authors tabulated insertion times, as well as complication and success rate based on anatomic dissection.

Tube type was randomly assigned for each attempt by each resident. One blunt insertion and one sharp insertion were performed on opposite sides of a cadaver each month for the trainees. Over a period of 5 months, each resident performed 10 total insertions.

Here are the factoids:

- Mean time to insertion for blunt vs sharp tips was the same, about 60 seconds

- Insertion time declined by about 20 seconds by the final attempt at 5 months

- Accurate placement occurred in 94% of blunt tip tubes vs 86% of sharp tip tubes

- There were significantly more complications with the sharp tip (4 below diaphragm, 5 outside the thorax, 1 in the liver, and 4 in the spleen) vs the blunt tip (2 below diaphragm, 2 extrathoracic, 2 in the liver, and 2 aborted due to damage to the tube)

- BMI did not increase complications, but it did increase insertion time significantly

The authors concluded that there is a 6-14% complication rate that is operator related, and that the incidence of complications was increased with the use of a sharp tip tube. They warn against the use of these tubes.

Bottom line: This is certainly an interesting study. The insertion numbers are sort of reasonable, and the use of fresh cadavers is okay. They are not quite as realistic as real living people, but close. The biggest drawback was that they used chest tube newbies, most of whom had never inserted a tube. And they were placed in the unrealistic setting where they had to attend training and watch a video, then insert two tubes per month without coaching or supervision. This is not how we do it in the real world.

I was impressed with what I consider the high number of complications. I don’t typically see that many, although I work at a blunt dissection institution. However, it does show that any trocar style tube is probably more like a weapon in inexperienced hands. So perhaps, even with supervision, both sharp and blunt trocar types should be avoided in the teaching setting. Sure, blunt dissection may take a bit longer, but the tube is also less likely to end up somewhere it shouldn’t be.

Tomorrow: Review of a “best evidence” review from New York.

Reference: Evaluation of performance of two different chest tubes with either a sharp or a blunt tip for thoracostomy in 100 human cadavers. Scand J Trauma Resus Emerg Med 20:10, 2012.