Earlier this year, I wrote a series of posts on the two commonly used pelvic fracture interventions: preperitoneal packing (PPP) and angioembolization (AE). To sum up, both are equally effective in controlling hemorrhage, but the hospital costs for patients undergoing angioembolization are significantly less. This is probably because there is no need to perform repeated operations to insert and remove the preperitoneal packs when angiography is used.

But what about venous thromboembolism risk? Patients with pelvic fractures are already at high risk for it. Couldn’t the increase in pressure on the pelvic veins or the use of thrombogenic materials increase the risk? Authors from several well-known trauma centers collaborated to re-analyze data from the CLOTT study. This is another cute acronym for an extensive study, the Consortium of Leaders in the Study of Traumatic Thromboembolism. It looked at the incidence and risk factors for VTE in trauma patients. This analysis focused on VTE risk in patients with pelvic fractures, comparing those undergoing one of the two interventions with those who had neither.

Here are the factoids:

- The original data were derived from a 17-center study conducted from 2018-2020; this study only included 1,387 patients who had pelvic fractures (as well as other injuries).

- The primary outcome was the development of VTE during the hospitalization. DVT was detected using duplex ultrasound, and PE was detected by CT angiography. If pulmonary clots were seen without concomitant DVT, they were not considered to be of embolic origin.

- For all comers, the overall incidence of VTE was 5.6%

- Breaking them down by type, there were 2.7% PE, 2.7% DVT, and 1.9% pelvic thrombi (some patients had more than one event)

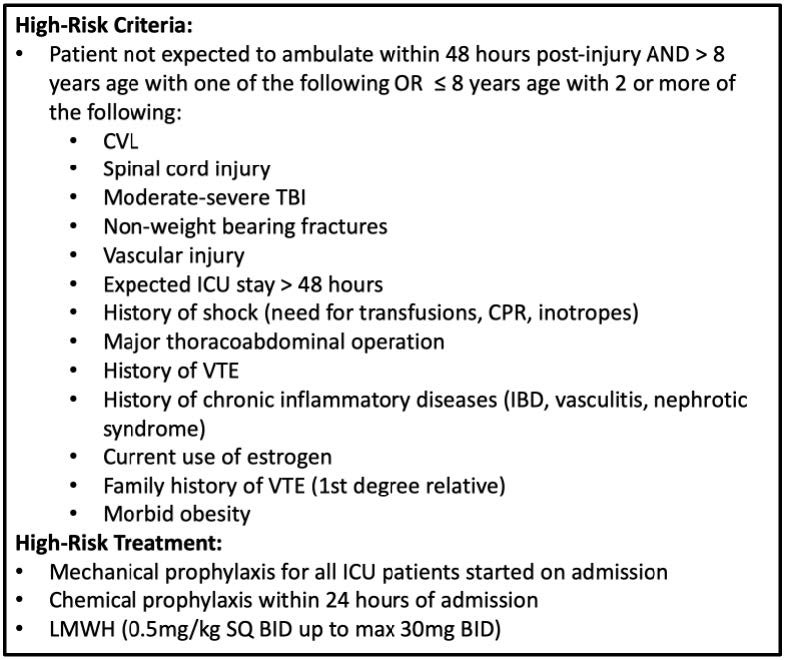

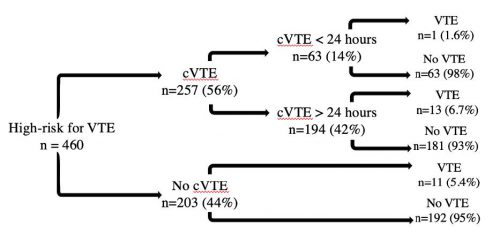

- Chemical prophylaxis appeared to be very effective. If started within 24 hours, the incidence was 2.9% vs. 8.4%* if started later.

- Missed doses did not appear to increase the incidence of VTE (about 5% for both groups)

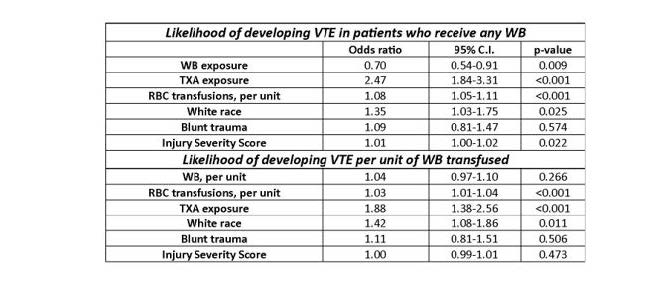

- Patients with PPP had a 9% incidence of VTE, pelvic angioembolization had 2.6%, and patients with ORIF had 16%. The incidence was 5.7% if no interventions at all were performed and 16% if more than one occurred.

Bottom line: There are a lot of tidbits in this paper. Most importantly, the use of PPP or AA does not significantly increase VTE risk. Interestingly, ORIF of the pelvis increases it. It’s not clear whether this is due to the procedure itself or is just a surrogate for the severity of pelvic injury. Multivariate analysis suggests that this is not a significant risk factor.

The finding that early chemoprophylaxis reduced VTE incidence to only 3% is very interesting. All too often, prophylaxis is delayed due to solid organ or head injuries. If it can be started safely in such patients, it should be to reduce the occurrence of this complication. One of the banes of management of major trauma is the potential need for repeated surgical procedures, which leads to a phenomenon known as “prophylaxis interruptus.” Thankfully, this study did not find that this increased VTE risk, although it did not stratify by how many doses were missed.

So put your mind at ease about increasing the risk of VTE risk by using procedures to decrease bleeding through mechanical means. But do remember to begin chemoprophylaxis soon and you safely can.

Reference: Does preperitoneal packing increase venous thromboembolism risk among trauma patients? A prospective multicenter analysis across 17 level I trauma centers. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 97(5):p 791-798, November 2024.