Seriously injured patients frequently develop coagulopathy, which makes resuscitation (and survival) more challenging. A few years ago, the CRASH-2 study lent support for using tranexamic acid (TXA) in select trauma patients to improve survival. This drug is cheap and has antifibrinolytic properties that may be beneficial if given for life-threatening bleeding within 3 hours of initial injury. It’s typically given as a rapid IV infusion, followed by a slower followup infusion. The US military has adopted its routine use at forward combat hospitals.

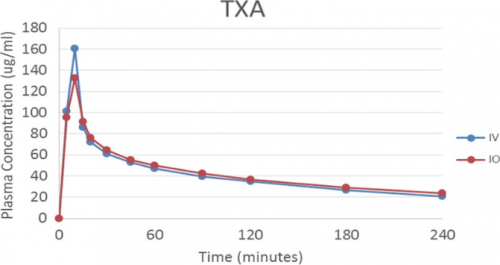

But what if you don’t have IV access? This can and does occur with military type injuries. Surgeons at Madigan Army Medical Center in Washington state tried using a common alternative access device, the intraosseous needle, to see if the results were equivalent. This study used an adult swine model with hemorrhage and aortic crossclamping to simulate military injury and resuscitation. Half of the animals then received IV TXA, the other half had it administered via IO. Only the bolus dose was given. Serum TXA levels were monitored, and serial ROTEM determinations were performed to evaluate coagulopathy.

Here are the factoids:

- The serum TXA peak and taper curves were similar. The IV peak was higher than IO and approached statistical significance (0.053)

- ROTEM showed that the animals were significantly hyperfibrinolytic after injury, but rapidly corrected after administration of TXA. Results were the same for both IV and IO groups.

Bottom line: This was a very simple and elegant study. The usual animal study issues come into play (small numbers, pigs are not people). But it would be nearly impossible to have such a study approved in humans. Even though the peak TXA concentration via IO is (nearly significantly) lower, this doesn’t appear to matter. The anti-fibrinolytic effect was very similar according to ROTEM analysis.

From a practical standpoint, I’m not recommending that we start giving TXA via IO in civilian practice. We don’t typically see military style injuries, and are usually able to establish some type of IV access within a reasonably short period of time. But for our military colleagues, this could be a very valuable tool!

Reference: No intravenous access, no problem: Intraosseous administration of tranexamic acid is as effective as intravenous in a porcine hemorrhage model. J Trauma 84(2):379-385, 2018.