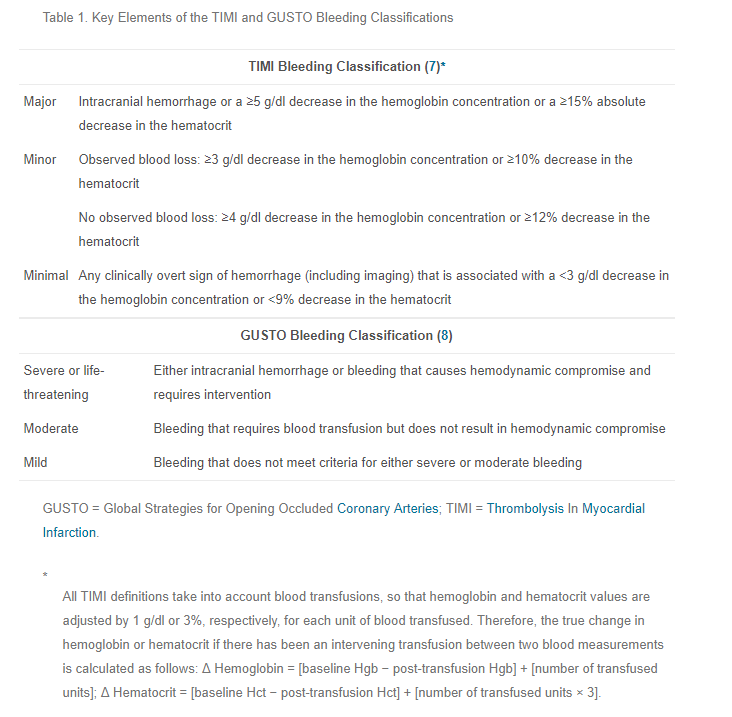

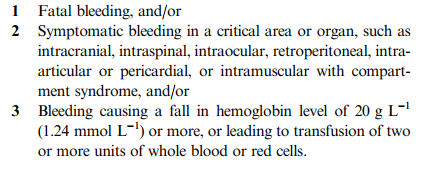

In my last post, I showed you some of the current definitions of “life-threatening” bleeding used in patients who are anticoagulated, as well as some for lesser degrees of bleeding. Confusing, right? How are we to ever know what is truly life-threatening so we can justify intervention/reversal with potent and/or expensive drugs and blood products?

It’s time for a more universal definition. The most important thing to recognize up front is that it is absolutely impossible to provide a comprehensive set of definitions that take every possible scenario into account. The list would be confusingly long. We really only need a few rules that are a bit more generalized. But then, how do we keep providers from just doing what they want, and coming up with some subjective or anecdotal justification? Bear with me for a day or two.

Today, I’ll lay out my two “universal definitions” of significant bleeding in an anticoagulated patient. Note that I didn’t say “life-threatening” bleeding. There is also such a thing as “limb-threatening” or “tissue-threatening” bleeding, and yet other ways to be harmed from uncontrolled bleeding due to anticoagulants.

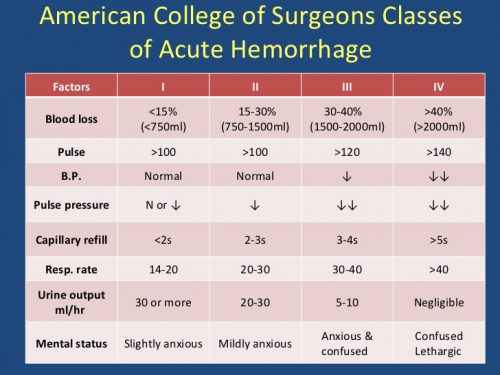

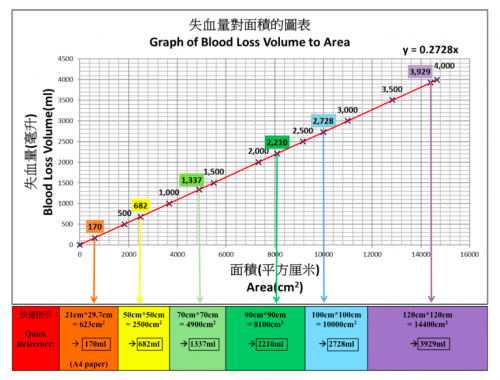

If you look through all the various criteria that I included in the last post, you can see that they generally fall into two categories: physiologic and anatomic. The key is to reach a balance of being specific enough without being overly so. This still allows for some degree of clinician judgment. But as you will see in my next post, there also has to be some type of scrutiny and review of that judgment.

So here is what I propose. Bleeding is considered significant and/or life-threatening if either of these are true:

-

(Physiologic) Bleeding that causes hemodynamic compromise (hemorrhagic shock) or changes in vital signs indicating progression toward it (increasing pulse rate, decreasing blood pressure).

-

(Anatomic) Bleeding into a body region or tissues that has a high likelihood of causing death, disability, or the need for operative intervention.

In my next post, I’ll show you how to operationalize these definitions into a workable process for making decisions about reversing anticoagulation.