A little further down the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) rabbit hole please? The abstract reviewed in my last post suggested that elderly patients taking these agents actually do better than those on warfarin. So if that’s the case, do we need to be so attentive to getting followup CT scans on these patients to ensure that nothing new and unexpected is happening?

The trauma group at UCSF – East Bay performed a multi-center review of the experience at “multiple” Level I trauma centers over a three year period. They included anticoagulated patients with blunt trauma who had a negative initial head CT. Patients taking only an anti-platelet agent or a non-oral anticoagulant were excluded. They analyzed the data for new, delayed intracranial hemorrhage, use of reversal agents, neurosurgical intervention, readmission, and death.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 739 records were studied: 409 on warfarin and 330 on a DOAC. Average age was 79, and half were male.

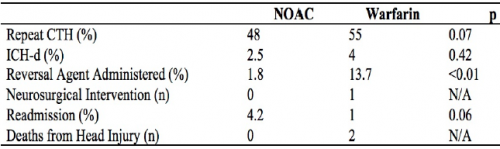

- Repeat head CT was performed only half the time (!)

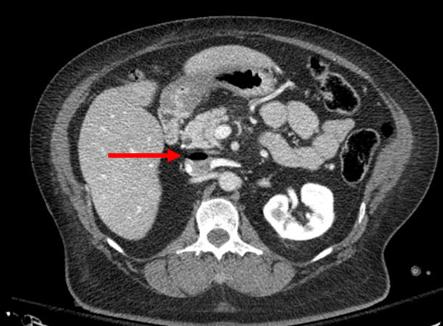

- Delayed hemorrhage was noted in 4% of warfarin cases (9 of 224) and 2.5% of DOAC cases (4 of 159)

- There were no interventions or deaths in the DOAC group with followup CT, or in those who did not have the repeat scan

- There was 1 intervention in the warfarin group and two deaths attributed to TBI

- Reversal agents were administered to 2% of DOAC patients and 14% of warfarin patients

- The authors performed a regression analysis that showed the two strong associations with delayed hemorrhage were male sex and AIS head > 2 (!)

The authors concluded that this “largest study” suggests that DOACs “may” have a better safety profile compared to warfarin and repeat head CT is not indicated.

Now, hold on a minute!

Rule #1: No single published paper should ever change your practice. They need to be confirmed by other, hopefully better work.

Rule #2: No single abstract should make you even think about changing your practice! These are preliminary works that always need more detail, more effort, and a lot more thought. They are meant to telegraph what the authors are working on and to raise interesting questions from the audience. They should stimulate others to try to replicate and improve upon the work. In general, if something looks really good as an abstract, the next step is successful publication. This means that peers have reviewed the data and agree that it looks promising. But then it should take several years of work by the original authors and others to prove or refute the claims.

This study was small in the first place, and became smaller because half did not have repeat CT scans. The only statistically significant result was that we confirmed that the providers were not very good about getting followup scans. Just because they didn’t do it doesn’t mean it’s not indicated, especially given the nature of the data and the very small numbers.

I consider this another very small piece in the puzzle that suggests DOACs are not as evil as warfarin. There are several of these low power studies floating around right now. But we need to hunker down and really do a big study right so we can start to get a clearer picture of what we should do. For now, it’s best to treat all anticoagulants and anti-platelet agents as evil and err on the side of overtreating.

Here are my comments and questions for the presenter and authors:

- Why was the followup head CT rate so poor? Was this a “however they like to do it” thing, was there a protocol, did the trauma centers just not believe that DOACs could be bad?

- What were the guidelines for reversal? If the initial head CT was normal, why ever reverse? This suggests that participating centers could do whatever they wanted based on unspecified criteria.

- Was the regression analysis helpful in any way? Being male and having a mild TBI seem rather nonspecific factors and wouldn’t help select patients for reversal or repeat scan.

- Please provide more information on the warfarin intervention and deaths.

- Isn’t the title of this abstract rather bold for the quality of the results presented?

I’m sure there will be some lively debate at the end of this presentation!

Reference: Repeat CT head scan is not indicated in trauma patients taking novel anticoagulation: a multi-institutional study. AAST 2019, Oral Abstract #66.