Minor complications from nasogastric tube insertion occur relatively frequently. Emesis is fairly common when the gag reflex is stimulated by the tube in the back of the oropharynx. An infrequent but possibly fatal one is insertion through the cribriform plate.

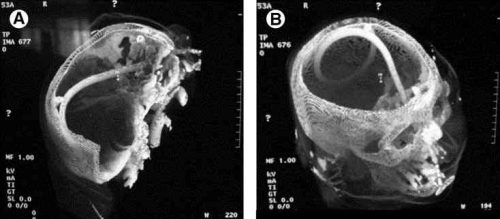

The cribriform plate is located directly posterior to the nares and is part of the ethmoid bone. It is very porous in nature and weaker than the surrounding portions of the ethmoid. It is easily fractured, and can be seen is association with basilar skull fractures. This is one source for rhinorrhea in patients with these fractures.

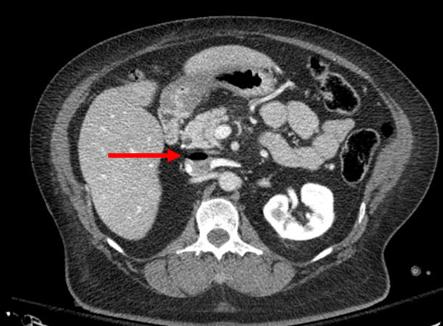

Cribriform fracture is a contraindication to unprotected insertion of a nasogastric tube. If you look at the sagittal section below, the plate lies directly behind the nares. When inserting the NG tube, we are usually taught to aim the tube straight back. Unfortunately, this aims it directly at the cribriform. If a fracture is present, it is possible that you may be inserting a nasocerebral tube!

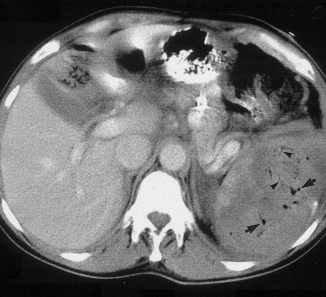

The usual symptoms when this occurs consist of immediate neurologic deterioration to coma, and a unilateral or bilateral blown pupil. The tube must not be withdrawn, because it will cause significant injury to the base of the brain. A stat neurosurgical consultation must be obtained, and if the patient is salvageable, the tube must be withdrawn through a craniectomy.

To avoid this dreaded complication, identify patients at risk for cribriform injury. They are:

- patients with signs of trauma from eyebrows to zygoma

- comatose patients

- patients with signs of basilar skull fracture (Battle’s sign, raccoon eyes, oto- or rhinorrhea)

If your patient is at risk, follow these guidelines:

- first, does the patient really need a gastric tube?

- if comatose, insert an orogastric tube

- if awake, don’t put the tube in their mouth, as they will gag continuously. Instead, place a lubricated, curved nasal airway. Then lube up a slightly smaller Salem sump tube and pass it through the airway.