Penetrating injury to the diaphragm, and specifically stab wounds, have been notoriously hard to diagnose since just about forever. Way back in the day (before CT), we tried all kinds of interesting things to help figure out if the patient had a real injury. Of course, we could just go to the OR and lap the patient (laparoscopy did not exist then). But the negative lap rate was significant, so we tried a host of less invasive techniques.

Remember diagnostic peritoneal lavage? Yeah, we tried that. The problem was that the threshold for red cells per cubic mm was not well defined. Some would supplement this technique with a chest tube to see if lavage fluid would drain out. And one paper described instilling nuclear medicine tracer into the abdomen and sitting the patient under a gamma camera for a few hours to see if any ended up in the chest. Groan!

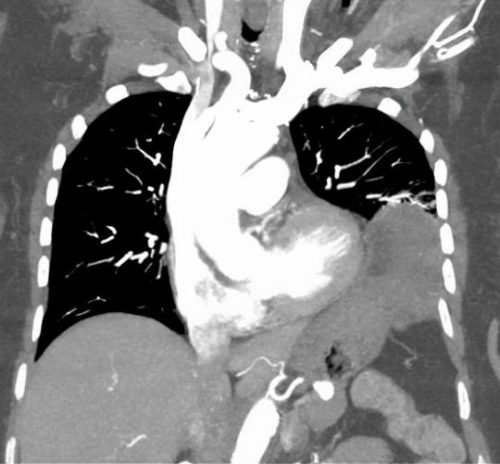

We thought that CT would save us. Unfortunately, resolution was terrible in the early years. If you could actually see the injury on CT, it was probably because a large piece of stomach or colon had already fallen through it. But as detectors multiplied and resolution improved, we could begin to see some smaller defects. But we still missed a few. And the problem is that left-sided diaphragmatic holes slowly enlarge over time (years), until the stomach or colon falls through it. (See below)

A group of radiologists and surgeons in a Turkish trauma hospital recently published a modest series of patients with left-sided diaphragm injuries evaluated by CT. They looked at about 5 years of their experience in a group of patient who were at risk for the injury due to a thoraco-abdominal stab wound. Unstable patients were immediately taken to OR. All of the remaining patients underwent an initial CT scan, followed by diagnostic laparoscopy after 48 hours if they remained symptom free.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 43 stable patients with a left thoraco-abdominal stab were evaluated

- 30 patients had a normal CT, and 13 had the appearance of an injury

- Of those who were CT positive, only 9 of 13 (69%) actually had the injury at operation

- Two of the 30 (7%) who were CT negative were found to have a diaphragm injury during followup laparoscopy

- So in the author’s hands, there was 82% sensitivity, 88% specificity, a positive predictive value of only 69%, and a negative predictive value of 93%

Bottom line: The authors somehow looked at the numbers and concluded that CT is valuable for detecting left diaphragm injury. Huh? They missed 7% of injuries, only finding them later at laparoscopy. And they had a 31% negative laparotomy rate.

Now, it could be that the authors were using crappy equipment. Nowhere in their paper do they state how many detectors, or what technique was used. Since it took place over a 5 year period, it is quite possible that the earlier years of the study used equipment now considered to be out of date, or that there was no standardized technique.

CT may not yet be ready for prime time. But it can be a valuable tool. Tune in tomorrow for some tips on how and when to look for this insidious injury.

Reference: Evaluation of diaphragm in penetrating left thoracoabdominal

stab injuries: The role of multislice computed tomography. Injury 46:1734-1737, 2015.