All right, let’s kick of this EASTfest with an abstract from one of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma multicenter studies. This one looked at outcomes after what they term “ultra-massive” resuscitation.

There are a number of definitions for “massive transfusion” which I’ve discussed before. They are basically trauma resuscitations in which the massive transfusion protocol is triggered. The group that designed this study defined ultra-massive resuscitation as one that entails transfusing at least 20 units of packed red cells within 24 hours.

The study focused on factors predicting survival in these patients. They used multivariate logistic regression as well as another regression tool, classification and regression tree analysis (CART). They used these tools to control for age, ISS, mechanism of injury, base deficit, and crystalloid use.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 400 patients were studied at 15 trauma centers over an eleven year period

- Subjects were young (mean 37 years), male (81%), severely injured (mean ISS 34) and in shock

- Median transfused products were 29u PRBCc, 23u FFP, and 24u platelets

- Mortality was high with half dying in 24 hours and two thirds not surviving to discharge

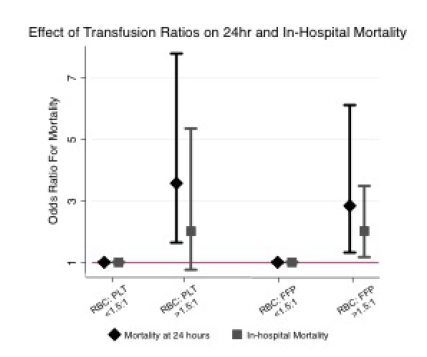

- Transfusion ratios > 1.5:1 for both RBC to plasma and RBC to platelets were strongly association with death

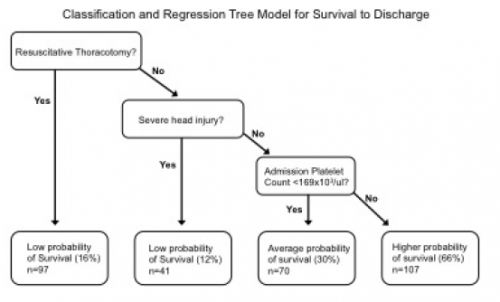

- CART identified severe head injury, resuscitative thoracotomy, and low platelet count (< 169K / microliter) we association with high mortality

- The best chance for survival occurred in those without a head injury, no thoracotomy, and higher platelet count

The authors concluded that the failure to meet balanced resuscitation goals was the main concern for mortality, and recommended more attention to meeting ratios.

My comments: I’m not so sure I’ve learned a lot from this abstract. I think we already knew that people with severe TBI or thoracotomy don’t do very well, especially if they need that much blood.

I also worry about the heterogeneity of the population. The variables that were controlled still offer quite a bit of variability in the injuries and condition of these trauma patients. I think this will make it difficult to come to many solid conclusions when looking at something as crude as mortality.

Here are my questions for the authors and presenter:

- Why are there so few patients? An eleven year study with 15 centers participating means that each submitted less than 3 cases per year. Most busy Level I centers have many more than that in a single year. Was there some other kind of data selection or limitation that is not described in the abstract? Do you think there is enough power? See question 3 for more on this.

- How did you arrive at an admission platelet count threshold of 169,000/ul? This would seem to be a surrogate for something else going on, and I’m not sure what. But it just seems so arbitrary.

- The transfusion ratios are a bit confusing. For ratios less than 1.5:1, there are no error bars. Does this mean that every one of those patients survived? That’s remarkable if so. And the error bars for the groups with a ratio > 1.5:1 are perilously close to the 1 line, and they have quite a range. Is the statistical power really there to convincingly show a difference? This is the most interesting part of the abstract, so please expound upon it.

- Explain your use of CART. How did you determine the specific determine the specific thresholds used in the CART model? Why did you choose to use this tool? For my readers, here is the tree presented in the abstract.

- What is the real message of the abstract? We already know that if patients who have a severe head injury or get their chest cracked are probably not going to make it. The transfusion ratio information is somewhat interesting, but there is better quality data out there that defines acceptable ratios. The platelet count information… interesting. What more do you have?

I think there is a lot of potential in this dataset once you overcome the small numbers. I’m very interested in the authors’ presentation!

Reference: Ultra-massive transfusion outcomes in a modern era: an EAST multicenter study. EAST 2021, Paper 1.