An air leak is a sure-fire reason to keep a chest tube in place. Fortunately, many air leaks are not from the patient’s chest, but from a plumbing problem. Here’s how to locate the leak.

To quickly localize the problem, take a sizable clamp (no mosquito clamps, please) and place it on the chest tube between the patient’s chest and the plastic connector that leads to the collection system. Watch the water seal chamber of the system as you do this. If the leak stops, it is coming from the patient or leaking in from the chest wall.

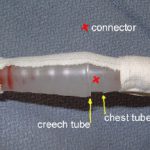

If the leak persists, clamp the soft Creech tubing between the plastic connector and the collection system itself. If the leak stops now, the connector is loose.

If it is still leaking, then the collection system is bad or has been knocked over.

Here are the remedies for each problem area:

- Patient – Take the dressing down and look at the skin entry site. Does it gape, or is their obvious air hissing and entering the chest? If so, plug it with petrolatum gauze. If not, the air is actually coming out of your patient and you must wait it out.

- Connector – Secure it with Ty-Rap fasteners or tape (see picture). This is a common problem area.

- Collection system – The one-way valve system is not functioning, or the system has been knocked over. Click here for an example. Replace it immediately.

Note: If you are using a “dry seal” system (click here for more on this) you will not be able to tell if you have a leak until you fill the seal chamber with some water.