It has been interesting to watch the evolution of the treatment of blunt thoracic aortic injury (BTAI). In my training, patients with an abnormal mediastinal contour on chest x-ray were whisked away to interventional radiology for a thoracic aortic angiogram. Yes, there was no such thing as a CT scan for anything but the head! Here’s a sample chest x-ray:

I wrote a post 12 years ago describing the various findings of a blunt aortic injury, many of which are present above. You can the post by clicking here.

In the 1-2% where the angio was positive (yes, you read that right; we did a lot of negative angiograms) the patient was then whisked off to the OR for an open aortic graft via thoracotomy. The advent of CT scans of the torso and improving resolutions allowed us to be more selective with angiography. And finally as CT angiography matured, aortic angiography became a thing of the past.

Then came TEVAR about 20 years ago. There were some growing pains as we refined the technology, but now this endovascular procedure is the standard of care for most aortic injuries. While there was also a place for nonoperative management, it was really just maintaining a reasonably low blood pressure to protect the vessel while getting the patient into good enough condition to tolerate anoperation.

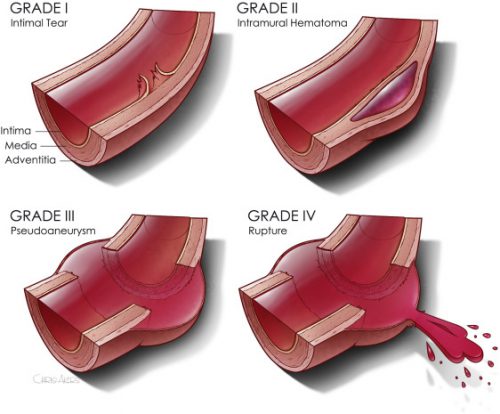

Now we are beginning to slice and dice treatment based on grade. Many centers have recognized that an intimal injury (Grade I) is only a very minor disruption to the inside of the vessel and does not make it more susceptible to rupture. Grade II management has been less clear. Here is a diagram of the various grades.

It makes sense that an invasive procedure may be less helpful for injuries that do not disrupt the layer of the vessel that provides its strength. But remember, common sense isn’t always the truth.

The group at Dell Seton Hall reviewed all patients with low grade BTAI (Grades I and II) in the Aortic Trauma Foundation Registry for a six year period. Their hypothesis was that these injuries could be successfully treated with medical management alone. They reviewed the data for mortality, complications, vent days, and lengths of stay.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 880 patients were enrolled and 274 had low grade injuries; 5 were then excluded when their lesion progressed and they underwent TEVAR

- Of the 269 remaining patients, 81% were treated with medical management (81% Grade I, 19% Grade II) and the remainder with TEVAR (20% Grade I, 80% Grade II)

- Rates of thoracotomy, craniectomy, and sternotomy were the same in both groups, but TEVAR patients were more likely to have a laparotomy (31% vs 15%)

- Mortality was significantly higher in the TEVAR group (18% vs 8%) but the mortality from the aorta was not quite significant (4% vs 0.5%)

- Complications (DVT and ARDS) were also significantly higher in the TEVAR group

- Vent days and lengths of stay were equivalent

The authors concluded that medical management alone is safe and appropriate, with a lower mortality and decreased complications compared to routine TEVAR.

Bottom line: Hmm, color me skeptical. Remember, this is a registry study, so information tends to be limited outside the usual demographics and data points that are very pertinent to the purpose of the registry. The most important concept is that the patients in each group must be identical in every way except for the intervention.

We can try to make them as identical as possible by matching pairs or subgroups of patients. But the biggest problem is that the number of patient characteristics that might be important to match may not be available for analysis in the database.

When the patients were initially treated at contributing centers, there were no specific rules that the individual surgeons had to follow to decide between medical management and TEVAR. They could pick and choose based on their own experience. Could the surgeon have recognized some patients as higher risk and opted for TEVAR to make sure the aorta would not become an issue in conjunction with their other injuries? And unfortunately, perhaps that higher risk issue is what ultimately killed them and not the aorta. It’s basically a form of unhealthy user bias.

This abstract is an interesting tidbit that should push us to question whether medical management is better, at least in some subsets of low grade aortic injury patients. Then someone can perform a more robust study to confirm or refute its safety. Unfortunately, this may never happen due to the low incidence of this injury. It took six years to accumulate only 269 eligible patients in this registry!

Here are my questions for the authors and presenter:

- What data points are actually in the registry? Specifically, is there fine detail about the other injuries the patient had? Could these have contributed to TEVAR mortality, or the selection of the patient for TEVAR to try to reduce the perceived mortality risk?

- When you stated that there was “no difference in demographics or mechanism of injury” what were these, exactly?

- What did patients actually die from in the Grade I and Grade II groups? Be more specific than “aortic-related” or not.

- Do you have any worries about the five patients whose lesions progressed? When should patients be re-scanned to identify those who might benefit more from TEVAR?

This is a thought provoking abstract, and I am very interesting in hearing what the next steps should be.

Reference: MEDICAL MANAGEMENT IS THE TREATMENT OF CHOICE FOR LOW GRADE BLUNT THORACIC AORTIC INJURIES. Plenary paper #45, AAST 2022.