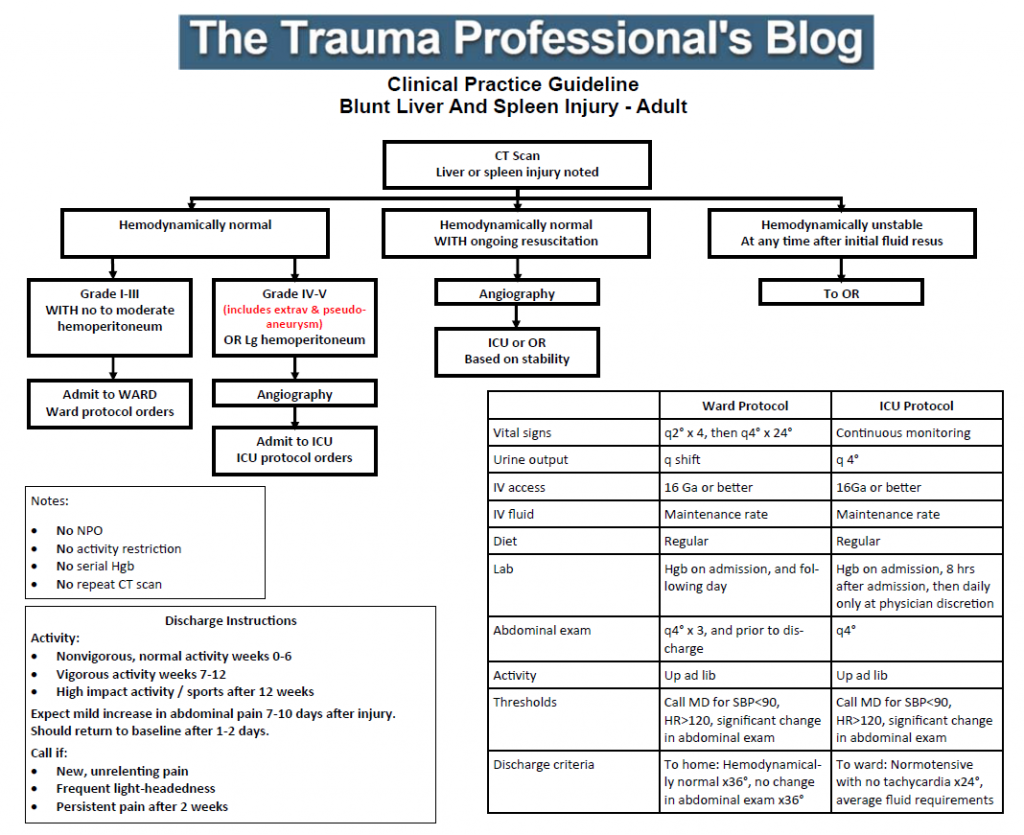

Regions Hospital developed a clinical practice guideline for solid organ management in 2002-2003. It has been revised a few times over the years, as any good guideline should with the availability of new data.

I’ve just put the finishing touches on the latest revision as a result of the updated organ scaling rules published by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. I reviewed the new scales for both liver and spleen earlier this year (links below). In the previous iteration of the scaling system, the importance of contrast pooling (pseudoaneurysm) or extravasation beyond the organ was not well defined.

The new guideline explicitly includes these injuries in the high grade group, which for us is grade IV or V. Technically, pseudoaneurysm of the liver is only grade III, but in my opinion demands angiographic investigation and embolism. Thus the inclusion in the high grade / angiography arm of our guideline.

For those of you who have not seen this guideline before, there are several important directives that are listed on the left side of the page:

- Patients are NOT made NPO

- They do NOT have activity restrictions (such as bed rest)

- Serial hemoglins are NOT drawn

- An abdominal CT scan is NOT repeated

These changes were made in 2015 based on our clinical experience that properly selected patients almost never fail. And they still don’t, so why starve, restrain, poke, and re-irradiate them?

Additionally, we included explicit impact activity restrictions for post-discharge so that patients would get the same message from all members of our team.

Click the image below to download the guideline and have a look. I’m interested in your comments!

Related posts: