Here’s the final post on my series covering serial hemoglobin testing in the management of solid organ injury.

We developed our first iteration of a solid organ injury practice guideline at Regions Hospital way back in 2002. It was borne out of the enormous degree of clinical variability I saw among my partners. We based it on what little was publicly available, including an EAST practice guideline.

Recognizing that the EAST guideline couldn’t dictate bedside care, we gathered together to meld it with our own clinical experience. We fashioned our first practice guideline later that year and tested it. It included instructions for bedrest (only overnight), vital signs monitoring, and lab testing (on admission and once the next day).

That last bit about serial lab tests is an important one. We had seen anecdotal evidence in our patients that it wasn’t very helpful. For example, I had one patient in the ICU whose serial Hgb had just returned normal. However, a minute later they experienced a hard hypotensive episode, and I took him immediately to the OR and took out a ruptured and bleeding spleen.

I’ve written several posts on how quickly Hgb changes after hemorrhage. Unfortunately, this lab test just lags too long to be a reliable indicator of anything. A very recent study has been published by Texas Health Presbyterian in Dallas. The retrospectively reviewed patients with liver or spleen injury over five years. They examined how often serial hemoglobin determinations influenced management during the study period. Possible interventions were none, operation, angioembolization, or blood transfusion.

Here are the factoids:

- There were 143 patients enrolled, and half had no interventions, a third had interventions within 4 hours, and the remainder (16%) had an intervention after 4 hours

- In the early intervention group, one-third underwent laparotomy, 42% angiography, and 9% had both; 17% received transfusions based on clinical parameters alone and not lab results

- Of the 16% that did have a later intervention (23 patients), 12 received a blood transfusion only based on a Hemoglobin value, and all but one had no further interventions. That patient had a laparotomy based on the lab test.

- All other patients in the late intervention group went to OR or angioembolization based on hemodynamics or a change in physical exam.

- The number of blood draws was phenomenal, with an average of 19 in the early intervention group, 17 in the delayed intervention group, and 7 in the no-intervention group

The authors concluded that serial hemoglobin measurements were not well-supported by the literature and that the decision for intervention was nearly always driven by hemodynamics or physical exam.

Bottom line: Although this study is small, the results are very clear. As we were taught in our surgical training, hemodynamics and physical exam are vital in managing solid organ injury. Unfortunately, hemoglobin is a lagging indicator, and the repeated discomfort and unnecessary cost overshadow its clinical value. This is most significant when treating pediatric patients.

Try to recall the last time you and your trauma colleagues had a patient whose need for intervention was based on a lab draw. Now take your practice guideline back to the drawing board and eliminate the serial exams!

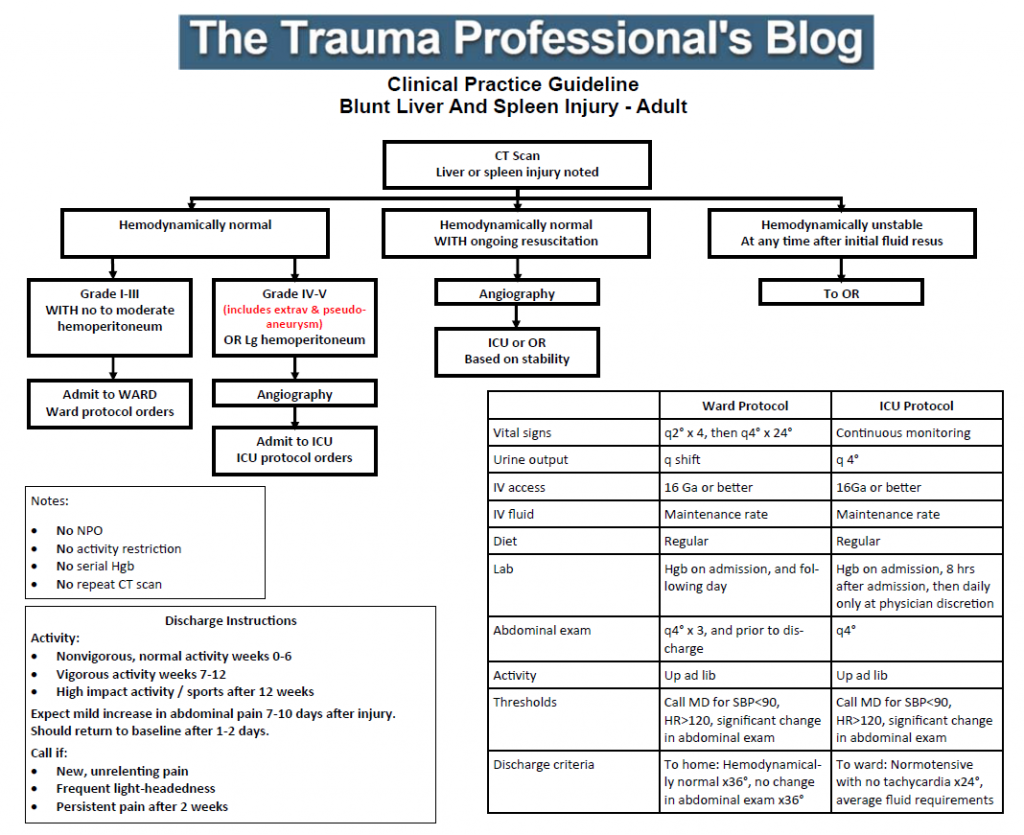

Click here for an example of a serial Hgb-free solid organ injury practice guideline

Reference: Role of Serial Phlebotomy in the Management of Blunt

Solid Organ Injury in Adults. J Trauma Nurs 30(3), 135–141, 2023.