New Technology: The End Of Handwashing?

All healthcare professionals are notoriously bad about washing their hands, especially doctors. A variety of things have been developed to help us keep our hands clean, including simple soap and water, barriers like gloves, and various gels and foams (which I swear I can taste in my mouth 10 minutes later, even though I’m pretty sure I’m not putting my fingers there).

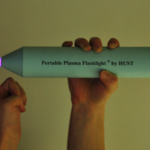

A recently published paper from China is shining new light on this topic (get it?). Researchers developed a hand-held, battery-powered plasma flashlight that gets rid of bacteria on skin in a flash. It costs less than $100 to produce and runs on a 12V battery.

This device was found to inactivate all bacteria in a 17-layer biofilm containing a very hardy organism, enterococcus faecalis. It does not produce UV radiation, and the exact mechanism for the bacterocidal effect is unclear. There was no adverse effect on skin.

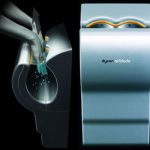

The main drawbacks to this device are that it only produces a small area of plasma, and it takes 5 minutes to kill all the bacteria. But take this to the next logical step. Many of you are familiar with the Dyson Airblade hand dryers found at many airports. Suppose you could produce a more intense plasma field using a more robust power supply (power line or ambulance power system) in a device that you could just pass your hands through to disinfect them?

And if you really want to improve compliance, hook the unit to the door control so the doctor can’t even walk into a patient room without passing his hands through it!

Reference: Inactivation of a 25.5µm Enterococcus faecalis biofilm by a room-temperature, battery-operated, handheld air plasma jet. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 45(2012):165205 (5p), 2012.