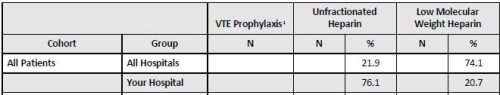

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is always a concern in trauma patients. But patients with spine fractures are at much higher risk and those with spinal cord injuries on top of it even more so. The best tool we have right now for prevention is chemoprophylaxis with some type of heparin. Unfortunately, VTE prophylaxis is commonly interrupted or delayed due to concern for causing bleeding. These concerns may relate to concomitant injuries (e.g. solid organ injury) or necessary surgical procedures.

About five years ago, the Army provided a $4.25M grant to fund the Coalition of Leaders in Thromboembolism (CLOTT) study group. It involved contributions from 17 Level I trauma centers attempting to look at the incidence, treatment, and prevention of VTE after trauma. Additional phases are now under way to look at offshoot discoveries from the original research.

A group from the University of California – Sand Diego performed a secondary analysis of a subset of the CLOTT study in patients age 18-40 over a three year period. Patients with a diagnosis of spinal cord injury who were admitted for at least 48 hours were analyzed. The authors focused on timing of the start of VTE prophylaxis, VTE rates, and missed prophylactic dosing. They also reviewed any bleeding complications.

Here are the factoids:

- From the entire CLOTT study group, 343 met criteria and had sustained a spinal cord injury

- Most subjects were young (mean 29) and male (77%) and had sustained blunt injury (79%)

- A total of 44 patients (13%) developed VTE – 30 DVT, 3 pulmonary embolism, and 11 pulmonary thrombus

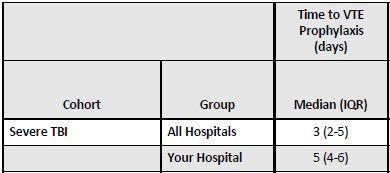

- Only one in five patients started chemo-prophylaxis prior to 24 hours, and this increased to about 50% at 48 hours (!)

- VTE rate overall was 9.6% (?)

- The rate trended lower in patients who received their prophylaxis within 48 hours (7% vs 13% but not significant)

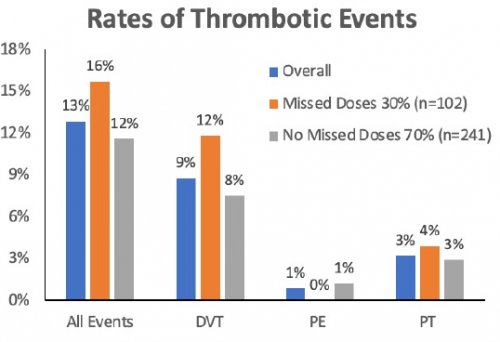

- Missed doses of chemo-prophylaxis were common (30%) and were associated with higher VTE rates

The authors concluded that VTE rates are high in these patients and early chemoprophylaxis is critical in limiting thrombotic events.

Bottom line: Hmm. This abstract confuses me a little. Actually, I had expected a higher VTE rate in this patient group. I’ve seen reports 2x to 3x higher than reported here. But yes, I do believe that these patients are at high risk.

And looking at the chart, it appears that there is a trend toward higher rates in patients who missed doses rather than those who did not. But the real questions are:

- Is it real? That is, are those differences significant? The only analysis in the abstract compares early vs late administration and that is trending toward significance but didn’t quite make it there. And remember that the graph you are looking at cuts off at 18% which makes the differences look much bigger.

- What can we do about it? Many trauma professionals are still uncomfortable giving prophylaxis early because of fear of bleeding. This is probably unwarranted, but we just don’t have enough hard data to say so. Anecdotal data about surgeons operating uneventfully through chemoprophylaxis is growing, though.

My impression of this study is that it shows some interesting trends, but probably doesn’t include enough subjects to know the real answer for sure.

Here are my questions for the authors / presenter:

- Tell us about the statistics. How did you calculate the rates that are cited in the paper? I can’t figure out the math.

- What is the difference between a pulmonary embolism and pulmonary thrombus? Is it merely the presence or absence of concomitant clot in the legs or pelvis? Why distinguish between the two if you are lumping them all together as “VTE?”

- What are we to do with this data? Obviously, everyone wants to provide VTE prophylaxis in a timely manner. But there are a raft of reasons why clinicians are “not comfortable” doing it. Any suggestions?

Reference: VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM RISK AFTER SPINAL CORD INJURY: A SECONDARY ANALYSIS OF THE CLOTT STUDY. Plenary Paper 23, AAST 2022.