When it comes to repeat CT scanning after splenic injury, there are believers and there are non-believers. In my experience, the majority of centers in the US are non-believers. However, there is a new paper in press that attempts to convince us that more should become believers.

I think the biggest lesson to be learned from this paper is that WE SHOULD READ THE ENTIRE PAPER before drawing conclusions. I have said this in the past and I will say it again. In this case, not only did I read the entire paper, but I had to dig deep into the references it cited as well.

Nonoperative management of splenic injuries has a very high success rate if done properly. Some papers claim this can be up to 93%, which parallels my experience. This success rate involves excluding unstable patients (they need to be in the operating room) and planned use of angioembolization in select patients. Over the years we have found that we need to do less and less in the management of solid organ injury patients:

- No bedrest

- No starvation (NPO status)

- No serial blood draws

- No repeat CT scan

- Few limitations on activity after discharge

For an example of a practice guideline that demonstrates that less is more, use the download link at the end of this post.

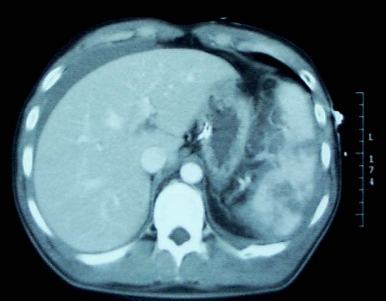

But back to the question about repeat CT scanning before discharge. Why do we need to do this? The usual reason is that “we want to find delayed pseudoaneurysms.” And why is that important? “It might bleed!”

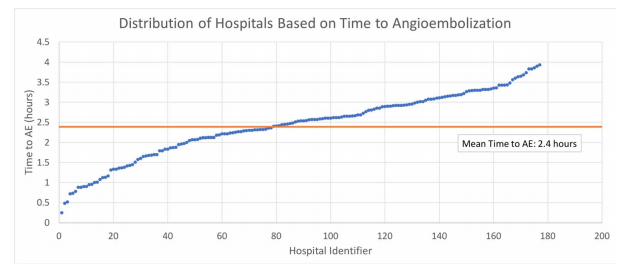

Really? Let’s look into that through the lens of this new paper by the group at the University of Cincinnati. They performed a retrospective study of their experience with patients who had sustained blunt splenic injury during a recent three-year period. They were interested in how many underwent splenectomy or splenorrhaphy, who had repeat CT imaging, who went to interventional radiology (IR) and when, and which ones were found to have pseudoaneurysms and what was done about it.

Here are the factoids:

- There were 539 patients who met inclusion criteria, with an average ISS of 24

- Of these, 46 died during their hospital stay (none from their splenic injury)

- Focusing on the 248 patients with higher grade injuries (III-V), 125 (50%) underwent emergent or delayed splenectomy. Early vs late operation was not broken out, but this is a startlingly high number!

- Of the higher grade injured patients who kept their spleens, 97% underwent repeat CT around day 5

- Delayed pseudoaneurysms were detected in the following patients:

- Grade III: 10 of 88 patients (11%). Then 8 of those 10 went to IR, and 5 of 10 had splenectomy!

- Grade IV: 7 of 24 (29%). Then 8 of the 7 (error in the paper?) went to IR and 3 of 7 had splenectomy!

- Grade V: 2 of 5 (40%). Both of these patients went to IR and somehow kept their spleens.

The authors conclude that routine followup CT imaging identifies splenic pseudoaneurysms allowing for interventions to minimize delayed complications.

Bottom line: Whoa! There’s a lot going on here. My first observation is that this center does a lot of splenectomies! Of the 539 patients (all comers) who were included in the study, 129 (24%) lost their spleens. If grade I-II injuries are excluded that percent rises to 50%!

Only eight splenectomies were performed after the repeat CT. This would imply that there were either a lot of unstable patients with splenic injury, the institutional indications for this procedure arbitrarily include grade, or there is a lot of variability in the decision to perform it.

I think there are really two questions to answer here.

- Does delayed splenic pseudoaneurysm occur? The answer is yes. There are a few studies (performed by believers) that demonstrate new pseudoaneurysms after repeat CT. I’m convinced.

- Do we care? The real question is, do these pseudoaneurysms cause harm? The fear is that they might explode at some point after patient discharge and cause a major problem.

Papers written by the believers cite a number of old studies and give numbers between 2% and 27% for incidence of delayed hemorrhage. Well, I tracked down all of these papers, including the ones they cited. And it doesn’t add up.

- One paper from a believer institution found no delayed bleeds.

- Several papers were for pediatric patients, whose spleens don’t behave like adult ones. They found one case after discharge in one out of 276 patients across three studies.

- Of 76 adolescents, none encountered delayed bleeds

Many of the papers cited regarding bleeding complications are very old. CT scanners had less resolution, and in many papers, IR was not even a consideration.

So here’s my take. Yes, delayed pseudoaneurysms occur. In children we don’t care. They almost never cause a problem. But in adults, they can and do cause issues and should be embolized shortly after the initial scan.

Once embolized, the ones seen on that initial scan are effectively neutralized and do not need a repeat scan. The small ones that might pop up later may very well be part of the healing process. And they may not even occur if angioembolization is done early. It seems unlikely that anything further is needed.

But remember, clinical judgement trumps all. If your patient starts complaining of new abdominal symptoms while in the hospital or after discharge, get a prompt CT scan to rule out any developing complications.

Sample solid organ injury protocol: click here

Reference: Delayed splenic pseudoaneurysm identification with surveillance imaging. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022 Mar 22. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003615. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35319540.