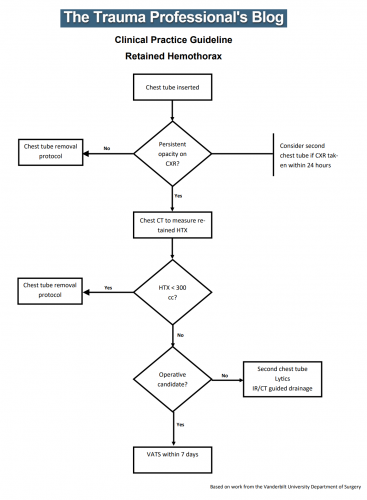

Over the last few days, I’ve reviewed some data on managing hemothorax, as well as the use of lytics. Then I looked at a paper describing one institution’s experience dealing with retained hemothorax, including the use of VATS. But there really isn’t much out there on how to roll all this together.

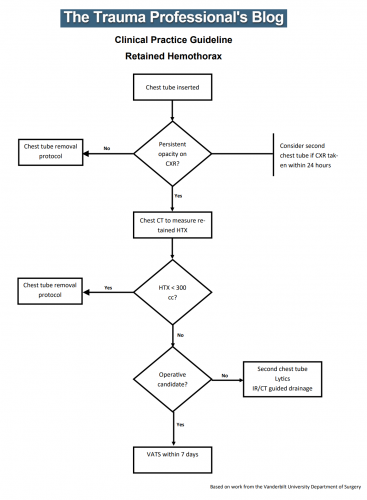

Until now. The trauma group at Vanderbilt published a paper describing their experience with a home-grown practice guideline for managing retained hemothorax. Here’s what it looks like:

I know it’s small, so just click it to download a pdf copy. I’ve simplified the flow a little as well.

All stable patients with hemothorax admitted to the trauma service were included over a 2.5 year period. The practice guideline was implemented midway through this study period. Before implementation, patients were treated at the discretion of the surgeon. Afterwards, the practice guideline was followed.

Here are the factoids:

- There were an equal number of patients pre- and post-guideline implementation (326 vs 316)

- An equal proportion of each group required an initial intervention, generally a chest tube (69% vs 65%)

- The number of patients requiring an additional intervention (chest tube, VATS, lytics, etc) decreased significantly from 15% to 9%

- Empyema rate was unchanged at 2.5%

- Use of VATS decreased significantly from 8% to 3%

- Use of catheter guided drainage increased significantly from 0.6% to 3%

- Hospital length of stay was the same, ranging from 4 to 11 days (much shorter than the lytics studies!)

Bottom line: This is how design of practice guidelines is supposed to work. Identify a problem, typically a clinical issue with a large amount of provider care variability. Look at the literature. In general, find it of little help. Design a practical guideline that covers the major issues. Implement, monitor, and analyze. Tweak as necessary based on lessons learned. If you wait for the definitive study to guide you, you’ll be waiting for a long time.

This study did not significantly change outcomes like hospital stay or complications. But it did decrease the number of more invasive procedures and decreased variability of care, with the attendant benefits from both of these. It also dictates more selective (and intelligent) use of additional tubes, catheters, and lytics.

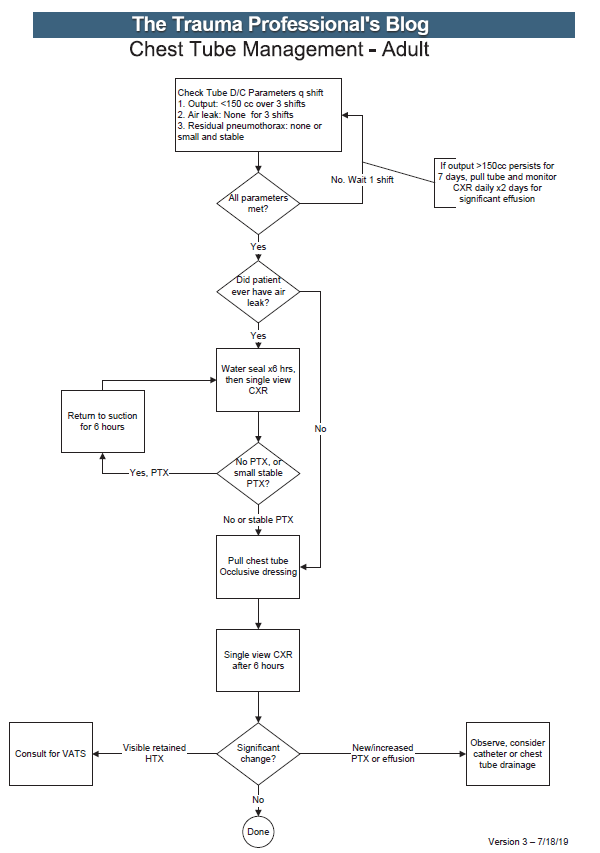

I like this so much that I’ve incorporated parts of it into the chest tube guideline at my center!

Download the practice guideline here.

Related posts:

Reference: Use of an evidence-based algorithm for patients with traumatic hemothorax reduces need for additional interventions. J Trauma 82(4):728-732, 2017.