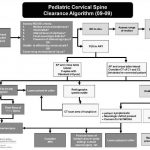

Algorithm For Clearing the Pediatric Cervical Spine

I previously wrote about a straightforward way to clear the cervical spine in children. Click here to see the article. Alfred I. DuPont Children’s Hospital has condensed their clearance technique into a relatively simple algorithm that can be used in conjunction with my previous tips.

Some notes on this algorithm:

- Can be performed only by attending physicians or a trauma resident in consultation with the attending trauma surgeon

- Clinical clearance alone may be carried out in select cases

- If radiographs are required, cross-table lateral, anterior/posterior, and odontoid views should be obtained (age 8 and above, non-intubated)

- Flexion / extension views should only be ordered in consultation with neurosurgery

Download a print version of the protocol here

Related post: How Do I Clear The Pediatric Cervical Spine?

Image and protocol courtesy of the Alfred I DuPont Children’s Hospital